FSO Safer: A profile of SMIT Salvage

The Dutch firm will conduct the operation to remove the oil from the Safer

When the UN announced in April 2022 that it would be going ahead with the two-stage operation to rescue the FSO Safer and prevent a potentially disastrous oil spill off the coast of Yemen, SMIT Salvage1 was identified as the party which would be handling the complex operation of extracting its 1.14 million barrels of oil onto a replacement vessel.

And on 19 April 2023 it was confirmed that a finalised agreement had been signed with the Dutch marine salvage firm; a day later it was announced that their vessel the Ndeavor was about to set sail for Yemen replete with the required crew and specialised equipment to conduct the salvage operation.

Their most recent notable operation was in March 2021 when it was called in by the Japanese owners of the Ever Given (chartered and operated by the Taiwanese firm Evergreen) to assist with the Suez Canal Authority’s efforts to dislodge the Ever Given from its grounded position in the Suez Canal; it ended up blocking off over 400 vessels for six days - around $US60B worth of trade - with an estimated knock-on effect of a 60-day shipping delay as many had to reroute around the Cape.

Yet this was just the latest in a series of high profile salvages of stricken vessels during its 180-year history.

Origins of SMIT Salvage

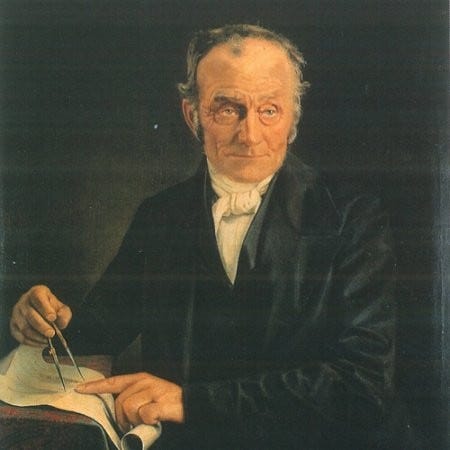

Fop Smit (1777 - 1866) was a shipbuilder and shipowner who contracted with 47 shipowners and insurers in Rotterdam in late 1842 to build a steam tugboat which would provide safe passage for other ships in the vicinity of Hellevoetsluis, an outport of Rotterdam. Less than a year later, the 140 horsepower paddle steamer 'Kinderdijk' was born. His tugboat business (he also ran a shipyard) at the time of his death in 1866 had a stable of 6 tugs.

The business, L. Smit & Co, was passed onto his sons and continued to expand into the 20th century - with some high profile salvages along the way (see below) - becoming L. Smit & Co.'s Internationale Sleepdienst and later Smit International. By the time it was acquired by Royal Boskalis Westminster for 1.15 billion euros in 2010, it was one of the largest marine salvage companies in the world.

What is salvage exactly?

In shipping or boating (as well as legal) terms, when a vessel gets in trouble out on the water and needs outside assistance to get it back to the safety of a harbour or the shore, it can be done either by towing or (the more expensive) salvage assist.

Towing a vessel (for example, due to mechanical failure, fuel or soft grounding issues) back to safety usually involves a situation where there is no imminent peril to the vessel itself, others in the area or the surrounding marine environment.

Salvage is a more complex operation and involves “the kind of dangerous situation at sea that will almost certainly inflict damage upon a vessel in distress if it is left subject to wind, waves, weather and tide without prompt salvage assistance”; it would usually occur after a fire, hard grounding, mechanical failure, collision or storm damage.2

What kind of services do SMIT Salvage provide?

They operate out of four centres in Rotterdam, Houston, Cape Town and Singapore and, according to their website, their core services include the following:

Emergency Response - Once called upon, their responsibilities would involve everything from assessment of the issue - using available vessel information and computer modelling pre-boarding, but also gaining insights after an actual physical inspection has taken place - to the planning and then execution of the required emergency response, all the while being in constant contact with the shipowners and relevant national authorities.

Wreck removal - When a vessel cannot be returned to shore in its original condition, it may involve everything from removing cargo on board (for example, fuel oil) to dismantling the vessel using specialised cutting equipment and lifting it out of the ocean to allow the wreckage to be recycled.

Environmental care - Vessels traversing the oceans can be carrying a variety of oils, chemicals and pollutants, which create a huge risk to the environment when the vessel runs into trouble, and so need to be extracted in the shortest possible time.

Preparedness & Prevention Services - SMIT Salvage offers a non-exclusive “pre-agreed Preparedness & Prevention Service” contract which lays out the terms, conditions and tariffs for a shipowner of any potential salvage operation before an incident occurs, including sharing of specific information beforehand such as technical ship drawings and fire fighting plans.

High profile operations

Besides assisting with the Ever Given, SMIT has been involved with many high-profile and high-risk operations, including but not limited to the following:

MV Modern Express

In late January 2016 the 164-metre long car carrier MV Modern Express was sailing from West Africa to France to deliver 3,600 tons of timber and assorted construction machinery when it crossed paths with heavy seas in the notoriously rough Bay of Biscay. As a result, it developed a 40-degree starboard list (essentially leaning at a 40 degree angle due to internal movements of its contents) and lost engine power.

With fears of its capsizing, all of its 22 crew members were airlifted off the vessel by the Spanish Search and Rescue under severe sea conditions. The French Navy took over as it drifted into its waters, sending a frigate and some hired tugboats; meanwhile the owners of the ship also called in SMIT Salvage who arrived along with further tugs. As the vessel began to drift closer to shore, where it would likely run aground somewhere in the Landes area, SMIT worked at trying to attach towlines so that it could be towed out to sea until a safe harbour had been found. After several attempts were thwarted by the cruel conditions, they were eventually successful during a milder weather window, only 48 kilometres off the French coast.

Spain volunteered the port of Bilbao as a safe haven to allow the Modern Express to be righted, which SMIT was able to achieve over a three-week period of ballasting and de-ballasting, as demonstrated in the video below. GCaptain also has a great photographic timeline of the salvage operation which can be found here.

Kursk

In August 2000, early into Vladimir Putin’s reign as Russian leader, an explosion on board the nuclear submarine Kursk caused it to sink to 108 metres below the ocean’s surface, resulting in all 118 crew being killed.

A year later, a joint venture between SMIT and Mammoet to resurface the submarine was formed and their efforts ended up with the Kursk being the heaviest object ever lifted up from such depths, when the operation concluded in October 2001.

A 24,000 ton deadweight barge was modified and established over the site, with the Kursk - its bow had to be cut off due to instability - then lifted up directly underneath using an array of lifting cables which had been attached to the Kursk after the drilling of 26 holes into the Kursk’s pressure hull. The barge was then transported over 140 kilometres to a drydock in Murmansk for later inspection by the Russian Navy.

MV Cabrera

The 100-metre long MV Cabrera was sailing through the Kafireas Strait on 24 December 2016 when it ran into bad weather and became grounded off the Greek island of Andros, breaking into pieces and sinking to 34 metres, along with its load of 3,500 metric tons of ferronickel and 200 tons of bunker fuel; all of its crew was rescued.

SMIT Salvage, along with its Greek partner Megatugs, were able to extract the fuel and some of the cargo. They were both later contracted to refloat the stern and some of the remaining cargo, which they completed on 22 October 2017 using a floating sheerleg crane. For more details, including some stunning visuals, see the video below:

Baltic Ace

On 5 December 2012, the 150-metre-long car carrier Baltic Ace, transporting a fleet of Mitsubishi cars from Belgium to Finland, collided with the container ship Corvus J and sank within 15 minutes, 65 kilometres off the Dutch coast near Rotterdam; 11 out of the 24 crew died, while the Corvus J stayed afloat.

To mitigate the environmental risks associated with the 1,417 cars and 540,000 litres of fuel oil onboard, as well as the dangers to marine traffic in the busy thoroughfare, in 2014 SMIT and its partner Mammoet Salvage was contracted to lift out the Baltic Ace, lying 35 metres below the surface, with the work expected to start in 2014 and be completed the following year due to winter months being off limits for salvage purposes.

The first phase in 2014 involved removing the oil and, because it had solidified, it needed to be heated first before being pumped out; 467,000 litres was eventually extracted over a two-week period.

In April 2015, the salvage operation commenced. After a detailed inspection, the original plan to lift the ship in six large sections was scrapped as the Baltic Ace was deemed too damaged. Instead, it had to be cut into eight segments using an 80-metre to 120-metre long cutting wire, with a bespoke approach required to get each segment from the sea. The operation, which involved 18 ships and 150 people, was finished in August 2015 and removed 13,000 tonnes of wreckage which was later recycled.

Other notable salvage operations

In January 1993, after facing heavy winds the Braer oil tanker hit rocks and ran aground off the Shetland Isles and spilled almost 85,000 tonnes (over 600,000 barrels) of crude oil. While most of the oil was swept out to sea, local wildlife was negatively impacted. A salvage attempt was made by SMIT but turned out not to be successful due to the conditions.

In January 1979, the oil tanker MV Betelgeuse caught fire and exploded off the West Cork Irish coast in an incident which came to be known as the ‘Whiddy Island disaster' in which 51 people, including 41 crew members, died. In an operation which took a year SMIT was able to salvage the wreck by lifting it up in four sections.

In January 2013, the mine countermeasures ship USS Guardian got stuck off a reef in the Sulu islands area of the Philippines due to monsoon conditions. SMIT first removed the over 56,000 litres of oil on board before cutting the hull into four pieces and lifting them onto a barge.

In December 2002 in the English Channel, the car carrier Tricolor hit the container ship Kariba in the early hours of the morning, with the former sinking; all of its 24 crew members were rescued by the Kariba. SMIT led an over year-long salvage operation commencing July 2003 which involved cutting the vessel into 9 sections using specialised cutting cable.

SMIT Salvage is a subsidiary of the Dutch company Smit International, itself a subsidiary of maritime services and dredging giant Boskalis.

Besides the existence of “marine peril” for a salvor to legally claim a reward, the service must be voluntary (with either no prior binding contractual arrangement already in place or not conducted by the likes of the coast guard) and actually be successful in saving persons or property (the principle of “no cure, no pay” usually applies), however there are exceptions for efforts to minimise environmental damage.

A salvage will take place under the auspices of either an “open salvage” (for example, using the ever decreasingly utilised Lloyd's Open Form where a reward usually based on a % of the recovered value is only known - and is thus “open” - after later arbitration) or a “pure salvage” contract (where an agreement is made beforehand).