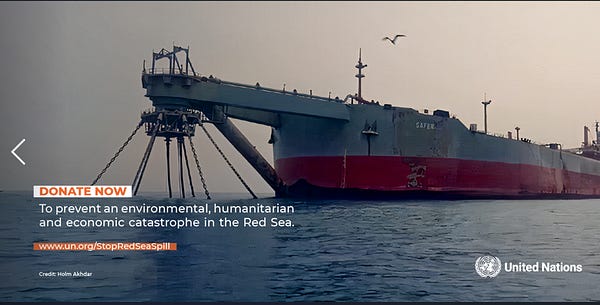

In June 2022 the United Nations announced that they were starting a crowdfunding campaign to raise funds for an ailing oil tanker off the coast of Yemen called the F.S.O. Safer, which was at risk of either blowing up, catching fire or sinking, and spilling around 1.1 million barrels of oil into the Red Sea.

While the story had been covered in the media and closely followed by Yemen civil society, activist groups and organisations, academics and the shipping industry, amongst others, it still brought a much needed boost of attention to the potential disaster and showed how far there was still to go.

The timeline below is an attempt to reflect key events in its story - past, present and future - including broader developments within Yemen. Publicly available sources such as news reports, the UN, activist groups, detailed original reporting particularly by Ed Caesar of the New Yorker but also others, are relied upon.

All errors and omissions are mine. Any corrections and tips are greatly appreciated.

1962

After the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire in 1917, the Mutawakkilite Kingdom of Yemen is established in North Yemen. Following an uprising inspired by Egypt’s President Nasser, the Yemen Arab Republic is born on 26 September 1962.

1967

On 30 November 1967, South Yemen - later officially named as the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen - is created after the four-year Aden Emergency, a guerrilla war aimed at ending British rule, culminates in the former colonial power leaving earlier than planned.

1976

The single-hull Esso Japan oil tanker build by the Hitachi Zosen Corporation is completed in 1976 and registered to Esso Tankers Incorporated. The steam-engine powered vessel comes in at a massive length of 350 metres (1,150 feet) and breadth of 70 metres (230 feet), with a Dead Weight Tonnage carrying capacity of just over 400,000 tons; fully-laden it can store up to 3.1 million oil barrels.

It belongs to the biggest class of tankers, the Ultra-Large Crude Carrier (ULCC) family, which are used for long distance haulage of crude oil and, due to their size, do not move through either the Panama or Suez Canals.1

1976 - 1982

The Esso Japan sees service across the world but can only really operate in deepwater ports in Europe and the Middle East, with occasional forays over to the Caribbean and the United States.

As the New Yorker’s Ed Caesar explains, when the tanker was being built during the 1970s, there was a boom in the construction of super-sized oil tankers. For almost eight years since the Six-Day War in 1967, the Suez Canal was closed and, with oil prices low, there was a big economic incentive to build huge oil tankers. But with the 1973 oil crisis creating a spike in prices and economic turmoil, and the Suez Canal opening up again in 1975, the need and appetite for accident-prone supertankers diminished. As he put it, “[t]he moment the Esso Japan left the shipyard, it was a dinosaur.” In 1982 the Esso Japan is sent to Ålesund, on the west coast of Norway, and effectively mothballed, along with about 250 other vessels that are no longer required.

1982 - 1986

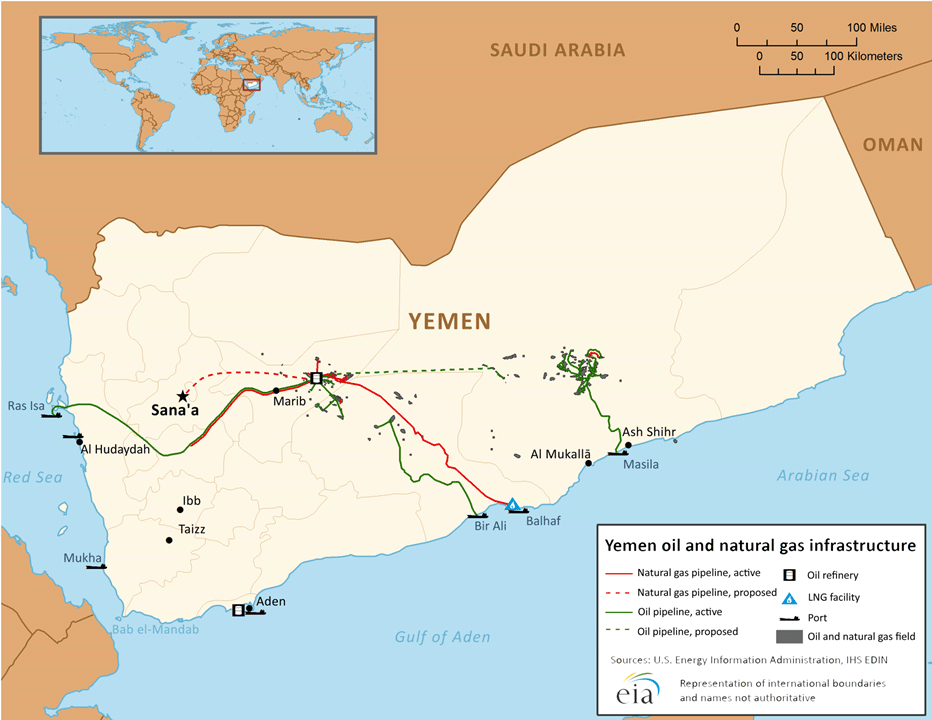

In 1981, the Yemen-Hunt Oil Company, a subsidiary of Hunt Oil Company, the legendary oil exploration and development company out of Texas, is given an oil concession in the Marib-Jawf area by the government of the Yemen Arab Republic (or North Yemen). The development area is located about 200 kilometres east of the capital Sana’a and 50 kilometres from the border with the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen (or South Yemen). A Production Sharing Agreement (PSA) is officially signed into law by the North Yemen Parliament in 1982 and allows for roughly 20 years of production, with an option to extend it for another five years.

A reconnaissance seismic program and geologic field mapping commences in 1982.

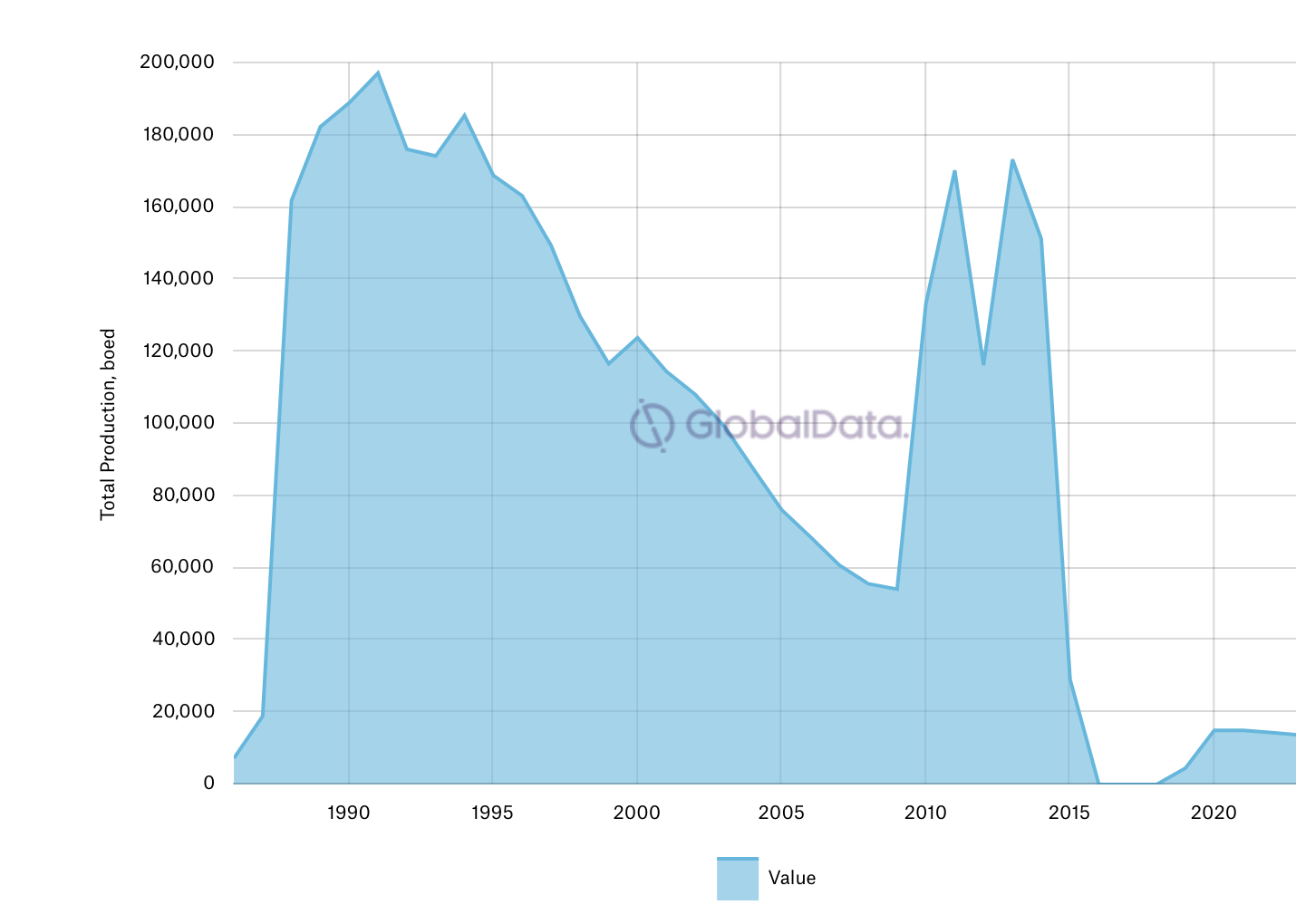

1984 sees drilling of the first well, Alif-1; subsequent appraisal and development drilling confirms the possibility of conventional oil production of a light grade oil referred to as ‘Marib Light’ from block Marib (Block 18). Other exploration leads to the discovery of 14 fields in the block. This is Yemen’s first ever discovery of crude oil reserves.

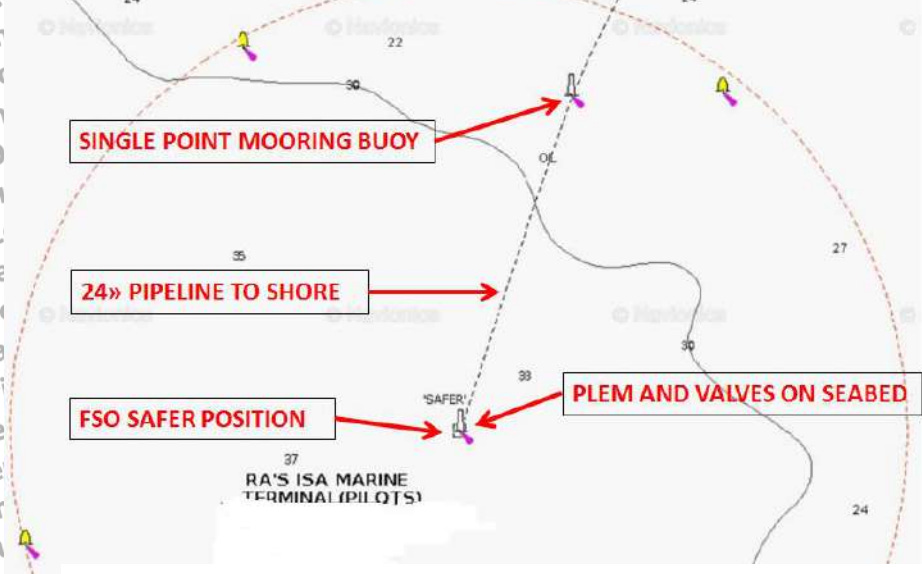

Plans commence for the development of the oil fields and the construction of the 438 kilometre Marib oil pipeline to take the proceeds from Block 18 to the Ras Isa marine terminal about 50 kilometres northeast of the port of Hodeidah. It is announced in 1985 that a joint venture between Exxon Corporation and Hunt called Yemen Exploration and Production Company (YEPC) is to be created for this purpose, with Exxon bringing their brain and muscle to the project.2

Around 1986 first oil begins to flow from the ground and, with the completion of the Marib pipeline (with capacity up to 200,000 barrels a day) in 1987, oil can now make its way to the Red Sea coast for export (with 1988 seeing a ramp up in production of oil to around 173,000 barrels per day).

1986 - 1989

As Hunt Oil Company anticipates the export of its oil after the development of Marib production facilities and the pipeline with the joint venture company, it is faced with the dilemma of what to do about creating facilities in Ras Isa for any required storage and export capabilities.

They come up with the following solution:

With only a limited licensed time for export available (15 years), to build a permanent fixture in place would take many years and come with a price tag in excess of US$100 million.

So instead, they decide to buy an oil tanker large enough to store large quantities of oil, park it off the coast of Yemen, run oil from onshore via an underwater pipe and retrofit it to enable it to be able to offload oil. At a cost of less than a tenth of a permanent facility on land, they would be able to facilitate the transfer of oil to vessels temporarily parked next to it in the harbour.

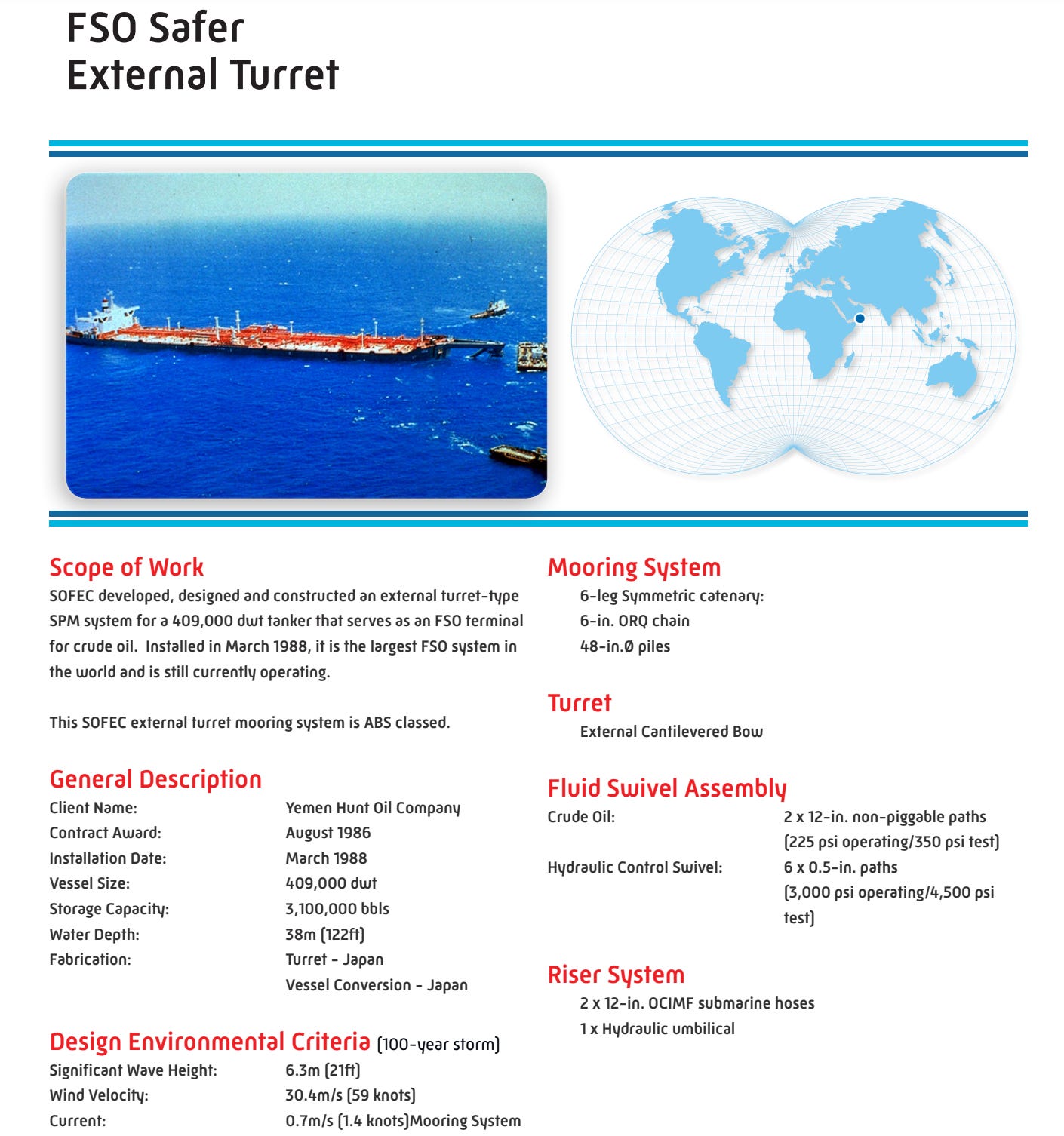

In 1986, the Esso Japan is purchased by Hunt for around US$10 million and renamed the FSO Safer (pronounced “Saffer”), after “a patch of desert near the city of Marib, in central Yemen”.

It makes its way from the waters nearby Norway over to South Korea for a US$12 million conversion into a FSO or Floating Storage and Offloading unit, including the fitting of an external turret mooring system “so that the ship could swing around its bow, like a weathervane, whenever winds kicked up, reducing strain on the hull”.

In 1987, south of Marib, in the South Yemen governorate of Shabwah, oil is discovered in a few fields by a former Russian company, with Canadian and French (Total) interests arriving for further development.

In March 1988, now ready for its new life in the Red Sea, the FSO Safer arrives off the coast of Yemen, about eight kilometres from the port of Ras Isa and is crewed by a mix of expats (mainly Italians) as well as locals, who work under apparently very good conditions onboard and relatively peaceful conditions onshore.

While the concept of the unification of Yemen has been on the cards for decades, with various initiatives having been undertaken, developments such as discovery of oil in Marib and Shabwah (and their attendant economic benefits) sees the two states begin serious talks in April/May 1988.

In May 1988 a demilitarised Joint Investment Area (JIA) is established between the two states to allow for joint exploration of oil fields between the Marib and Shabwah oil developments. In late 1989, talks about the formation of the Yemen Investment Company for Oil and Minerals (YICOM) - a five-party group consisting of Hunt, Exxon, Total, and two firms from Kuwait and the Soviet Union - reach their latter stages; final rounds of talks sees an agreement signed in December 1989 to explore and exploit the JIA.

1990 - 2014

The two nations merge to become the Republic of Yemen on 22 May 1990, with North Yemen’s President since 1978, President Ali Abdullah Saleh, named as the new President of the united country, with Sana’a as its capital. While the South holds a larger portion of the combined landmass, the North has a majority of the population.

After unification, discontent in the South about their deteriorating economic conditions and political marginalisation sees the outbreak of a civil war from May to July 1994 when forces in the South attempt to secede and form their own independent state; they are ultimately crushed by Saleh’s forces in the space of a couple of months.3

Oil production from the Marib continues to be exported via the Safer, but with declining yields.

In 2000, Hunt is given a five year extension at Ras Isa and the Yemeni government puts together a committee to come up with more of a permanent solution. Unfortunately, with an extremely hefty quoted price tag of US$1 billion for an onshore storage and processing terminal - allegations of corruption were voiced - it goes nowhere.

As part of the initial PSA with the North Yemen government back in the early 1980s, there was an option to extend the initial 20-year agreement by another five years if agreed to by both parties (with the united Yemen government now replacing the North Yemen government). As the end of the contract period approached, negotiations between the YEPC and the Yemeni Ministry of Oil go well enough that an agreement is signed in January 2004, with an effective start date in November 2005 the following year.

In June 2004, clashes start to occur between the Sunni-majority Yemeni government and the Zaydi-Shiite movement formed by ex-parliamentarian Hussein Badreddin al-Houthi in the late 1990s, as hundreds of followers are arrested. The Yemeni government accuses the Iran-supported movement of trying to restore the Zaydi Imamate that had once ruled North Yemen up until the 1940s, while the Houthis contend their culture and people are being suppressed.4 In September 2004 al-Houthi is killed by government forces and is replaced by one of his brothers, Abdul-Malik Badruldeen al-Houthi.

For the extension of the production agreement to actually be binding, the Yemeni Parliament needs to provide formal agreement as well just as with the original agreement. It seems that at some point in 2005 it is put to Parliament and approval is rejected, but YEPC still anticipates approval in time for the official extension in November and claims to have thrown millions of dollars into development in anticipation.

However, on the official commencement date of 15 November 2005 the Marib block is seized by the Safer Exploration and Production Operations Company (SEPOC) in light of the non-ratification by Parliament. By then, the block has produced one billion barrels of oil. Subsequent arbitration5 with the International Chamber of Commerce sees the Yemeni government win out over YEPC. Control of Marib oil production, now also along with pipeline and the Safer falls under the control of SEPOC. With SEPOC now in charge, the Safer continues to be maintained and operated, with an annual budget of US$20 million allocated to the FSO. Around 50 staff are employed on the vessel which continues to pass yearly inspections from the American Bureau of Shipping.

Between 2005 and 2010 sporadic fighting occurs between government forces and the Houthis. A Qatar-brokered ceasefire in June 2007 lasts less than a year before clashes recommence between April 2008 and July 2008. Then in August 2009 a fresh operation is launched by the government, with the Houthis also getting involved in skirmishes with Saudi Arabia, before another ceasefire is reached in February 2010.

In late January 2011 students gather and protest in Sana’a and other cities, inspired by the protests that began the previous month in Tunisia and ignited the “Arab Spring”. In response, President Saleh6 promises reforms and his future resignation, but deadly protests continue. Saleh eventually resigns on 23 November 2011 as part of a Gulf Cooperation Council-brokered agreement. His southern-based Vice President Abed Rabbo Mansour Hadi is given power. Hadi formally becomes President on 25 February 2012.

By 2012, revised plans for the Ras Isa onshore terminal culminate in a consortium led by the Dubai-based company ChemieTech beginning construction, with a more reasonable budget of less than US200 million this time around. It could not come a moment sooner as by this stage the Safer is really starting to show its age, with crews coming onshore relaying to a ChemieTech director their fears of it sinking. Yet two years later after work commenced, the onshore terminal would only reach half completion, because of dramatic events that would see Yemen reach new levels of crisis.

On 18 August 2014, after government removal of fuel subsidies, the Houthis call for mass protests. A month later, the Houthis advance on the capital of Sana’a and take control of key government buildings; most of the Yemeni army does not intervene.

On 21 September 2014 the UN brokers the “Peace and National Partnership Agreement” deal, with the Houthis and the Yemeni government to form a more inclusive government”; Prime Minister Mohammed Basindwa resigns a few hours before.

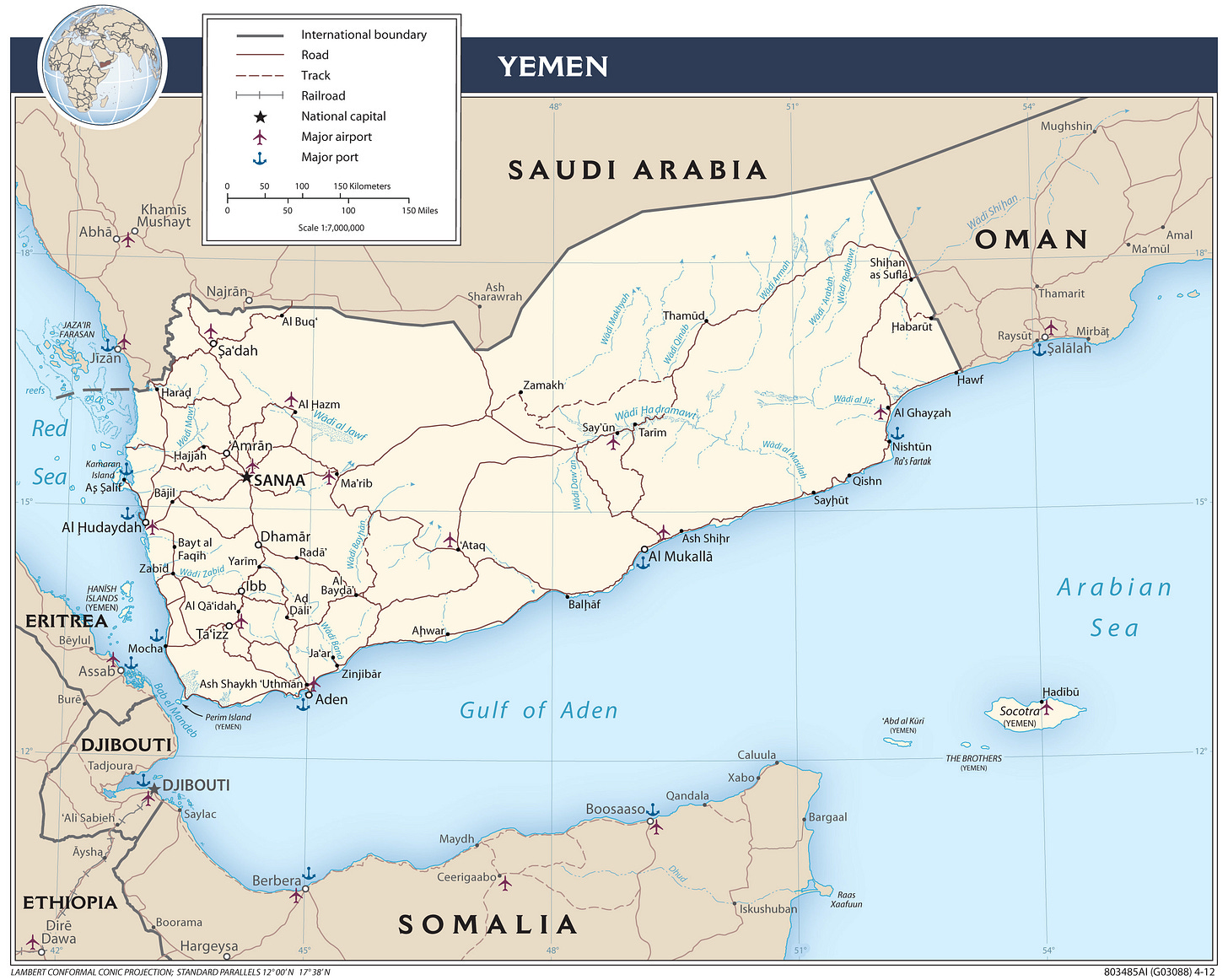

The Houthis seize the port city of Hodeidah on 14 October 2014, set up checkpoints and take control of the airport.

2015

President Hadi resigns on 23 January 2015, claiming that the Houthis have not honoured the peace deal, and is placed under houses arrest.

A month later Hadi, having escaped, reappears in Aden on 24 February 2015 and retracts his resignation.

Yet just another month later on 25 March 2015, Hadi flees his palace into exile in Saudi Arabia as the Houthis and army forces allied to Saleh enter Aden; despite earlier agreeing to go into exile, Saleh remains and joins forces with the Houthis. Yemeni Foreign Minister Riad Yassin calls on Arab nations to urgently intervene.

On 26 March 2015, a Saudi Arabia-led coalition of Gulf states and Egypt, with US and UK logistical, intelligence and arms support, launch air strikes against the Houthis ostensibly to protect the Yemen government. (An economic blockade and ground troops will follow later in 2015.) On 22 September 2015, Hadi returns to Aden from exile.

Things really begin to really deteriorate for the Safer after the Houthis take over the area near Hodeidah in March 2015:

The Houthis seize SEPOCs total operating budget of US$110 million, including the US$20 million for the Safer.

The port of Ras Isa closes in March 2015 along with many oil operations; although with a blockade being applied on the harbour by the Saudi-led coalition, this is a moot point.

By the end of 2015, only one foreign worker remains. All supporting vehicles like tugboats and helicopters are pulled out and a local fishing boat has to be hired to ferry the local crew to and from the Safer. Specialised underwater repair divers from Dubai are pulled out.

2016

The Houthis and Saleh form a 10-member political council on 28 July 2016 to run Sana’a and much of northern Yemen, split 50:50 between the Houthis and Saleh’s party; the UN condemns its formation.

With inspections by the American Bureau of Shipping no longer possible, the Safer becomes uninsurable by September 2016. Fuel oil levels for the steam boilers are also really low; not only is there no access to the usual fuel annual budget of US$5 million to US$8 million but, due to the war, the specific type of fuel needed is in short supply as well. What supplies remain are used irregularly and only to keep the fire-response and inert-gas systems running.

2017

By 2017 the Safer team run out of fuel completely, along with those essential safety functions, as well as the ability to power the large oil cargo pumps to extract the crude oil stored on board. With inert gases not able to be pumped into the storage tanks and neutralise the flammable emissions rising up from the oil, there is a heightened risk of an explosion if the fumes were to make contact with a spark, discarded cigarette or weapon fire. It is considered too risky to use the crude oil being stored on the ship to power the boilers due to potential emissions of dangerous gas. A couple of diesel generators are utilised, but for low level activities such as charging laptops. At some point SEPOC tries to sell the Safer for US$60 million due to the debts owed to Chemietech, but has no success.

Saleh is killed by the Houthis on 4 December 2017 following a three-day battle after he switches sides to the Saudi-led coalition.

2018

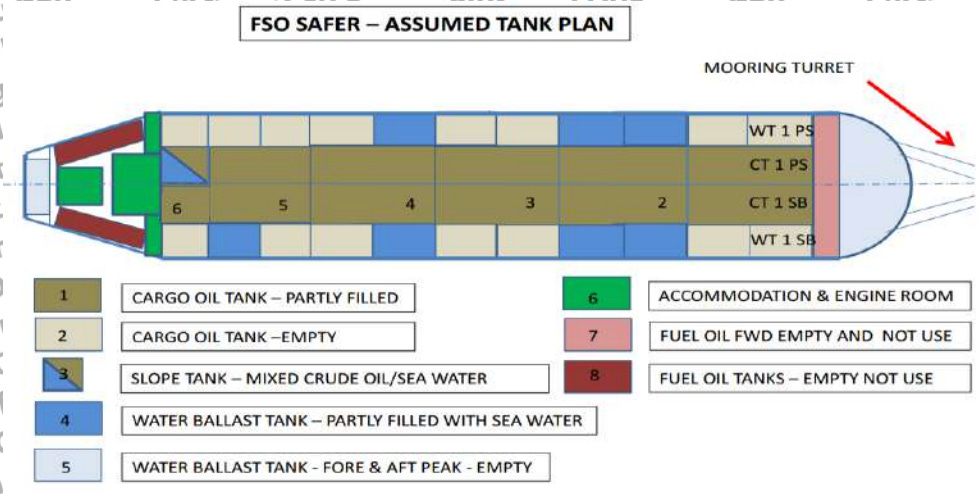

Come 2018, a skeleton crew7 with limited resources is left on board the Safer and swaps out every month when possible; conditions below deck are tough, with no ventilation or air-conditioning in a very hot environment. With the oil stored along the Safer's spine in 11 central storage tanks, SEPOC fills seven of the outside tanks with seawater as some kind of buffer in case stray munitions make their way over to the tanker. But with a combustible load on board, with no real fire safety team to speak of, it is a last ditched attempt at protecting the tanker, its crew and load.

March 2018

In March 2018, both the Houthis and the Yemeni authorities write separately to the UN seeking assistance on the matter of the Safer. It turns out that, technically, this is not really a task normally in the UN’s remit because of the expertise required and the Safer belonging to a commercial entity. Nevertheless, it gets passed onto the Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (and is picked up by John Ratcliffe, their Yemen specialist), the Office for Project Services (for hardware and expertise) and the UN special envoy to Yemen, Martin Griffiths. While not experts at all on oil tankers, Ratcliffe gets to work with the other teams, using his Office’s expertise “at setting up in-country humanitarian operations, mobilizing funding, and all of these kinds of things”.

June 2018 - November 2018

Yemen government forces, backed by the Saudi-led coalition, launch an assault on the 400,000 inhabitant8 port city of Hodeidah between 13 June 2018 and 23 June 2018; the operation pauses as the UN’s Martin Griffiths starts to hold talks with the parties.

Despite continued clashes on the outskirts of the city, a date of 6 September 2018 is set for talks between President Hadi and Houthi representatives in Geneva. 9 September 2018 passes with the Houthis a no-show and the Geneva talks are off, although the Houthis accuse the Saudis of putting obstacles in their way.

Fighting continues into October 2018 and escalates in November 2018.

December 2018

A partial deal between the parties to the Yemen conflict, brokered by Martin Griffiths, is signed on 13 December 2018 and comes to be known as the Stockholm Agreement, with the following three components:

The Hodeidah Agreement - “An agreement on the city of Hodeidah and the ports of Hodeidah, Salif and Ras Issa.”

A Prisoner Exchange Agreement - “An executive mechanism on activating the prisoner exchange agreement.”

The Taïz Agreement - “A statement of understanding on Taïz.”

Of most relevance to the Safer story is the Hodeidah Agreement:

In the lead up to the agreement there is fierce fighting for the city, including street fighting and aerial bombardments from the Saudis and anti-aircraft fire from the Houthis; Hodeidah is responsible for the majority of food imports into the country.

While the Houthis had controlled the city and port since 2015, to avert a total humanitarian disaster an agreement is made for a ceasefire at the port as well as the close-by ports of Salif and Ras Issa (the home of the Safer). This also represents an opportunity to try and get some traction on inspections of the Safer, and thus action on trying to resolve the increasingly dangerous situation on the ailing tanker.

The UN and the Houthis set about on a two-track course of talks, with John Ratcliffe as UN special envoy handling the politics, while on the technicalities the Office for Project Services (with assistance from an experienced private oil-tanker safety firm - A.O.S. Offshore) tries to set up an inspection of the Safer.

2019

April 2019

April 2019 sees the issue of the Safer first raised at the U.N. Security Council; the Council is briefed with any updates by Mark Lowcock, U.N. Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator.9

August 2019

Based on talks leading up to the summer of 2019, an accord is reached between the UN and the Houthis to give the UN team safe passage on their way to the Safer.

By August 2019, the UN is all set to go on their inspection of the Safer after getting all the approvals from the Houthis, with boats, crew, engineers and equipment waiting in Djibouti. But the night before, the Houthis send a text calling it off - because of an unrelated issue:

Since 2016, the UN has been administering the UN Verification and Inspection Mechanism for Yemen (UNVIM), which requires any sea vessels heading for any ports on Yemen’s Red Sea (Hodeidah, Salif and Ras Issa - not under the Yemeni government’s control10) to be inspected by the U.N. either in Djibouti or international waters, unless advance clearance has been granted.

The purpose is for the U.N., as requested by the Yemeni government, to make sure that no cargo such as weapons is being delivered to areas not under their control.

The Houthis, however, want any required inspections to occur in Hodeidah instead of Djibouti, and essentially used the scheduled visit to the Safer as a leverage point. The inspection does not go ahead.

2020

February 2020

The Safer is included in the UN Security Council’s Resolution 2511 on “The situation in the Middle East” and adopted on 25 February 2020:

Emphasising the environmental risks and the need, without delay, for access of

UN officials to inspect and maintain the Safer oil tanker, which is located in the

Houthi-controlled North of Yemen.

March 2020

In March 2020, a joint letter signed by Egypt, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Djibouti, Yemen and the Sudan is sent to the United Nations Security Council urging them to get the Houthis to open up the Safer for inspection.

May 2020

While only publicly reported on the next month, on 27 May 2020 the Safer nearly sinks:

A corroded pipe, linked to an external valve used for pumping seawater throughout the ship for cooling purposes (before being expelled), is found leaking seawater into the engine room.

The crew works for five days - a total of 28 hours under water - to try and stop the inflow, as well as also pump the water out of the engine room. An external team of divers - with no experience of oil tankers - manages to eventually fashion a steel plate over the external valve positioned underwater. This turned out to be a temporary fix though as water continues to still leak in and needs to be pumped out using the generators onboard.

After the incident, gun-toting Houthi soldiers come on board and also install surveillance cameras.

Later the UN purchases a one kilometre length self-inflating “oil boom” from NorLense, a Norwegian oil spill-response company firm, which if required basically can wrap around the Safer on the surface of the surrounding sea and start to absorb any spilled oil; it is transported to the region but not yet deployed due to lack of access given by the Houthis.

June 2020

The Associated Press (AP) release a report on 26 June 2020 that discloses the leak of seawater into the Safer engine room, based on a review of internal documents seen by the AP; it also details the rust scattered all over the ship and the fact that the inert gas has escaped from the storage tanks.

July 2020

Yemen’s foreign ministry issues a call on social media on 4 July 2020 for the UN to convene a session over the Safer.

After the mounting public pressure, on 15 July 2020 a special session of the UN Security Council is held on the Safer matter:

Inger Andersen, UN Under-Secretary-General and Executive Director of the United Nations Environment Programme, states that “[t]ime is running out for us to act in a coordinated manner to prevent a looming environmental, economic and humanitarian catastrophe”. She also emphasises that it is imperative that access be granted to inspect the Safer so that an assessment of its condition and determination of a solution to safely offload the cargo can be made.

Andersen also lays out some worst-case scenario conclusions from modelling11 conducted by the UK firm Riskaware and funded by the UK’s Department for International Development earlier in 2020:

100% of Yemen’s fisheries on the Red Sea coast would be affected within days (at a potential impact cost of $1.5 billion over 25 years).

Hodeidah port being closed for five to six months, resulting in 200% price increases in fuel and food prices, and a shifting away of food imports to Aden which would likely suffer from capacity constraints.

A fire would expose 8.4 million people to harmful pollution, as well as to populations from neighbouring Djibouti, Eritrea and Saudi Arabia.

The passage of more than 20,000 ships that traverse the Red Sea each year would be disrupted.

It is confirmed that the week before the Houthis have agreed in writing to allow inspections of the vessel within the next few weeks, with possible scope to include a technical assessment and initial repairs; the UN is working with member countries on raising money for the operation. (However, it is also noted that the Houthis had made similar assurances back in August 2019 and then reneged on it at the last moment.)

Mark Lowcock, UN Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator, advises that an offical request has been made to the Houthis the previous day to go forward with an inspection, including details of the plan, any technical equipment required and the relevant personnel; the team can deploy within three weeks of getting the requisite permits from the Houthis.

August 2020

Ahmed Aboul Gheit, the Secretary-General of the League of Arab States, on 10 August 2020 calls for the UN Security Council to take immediate action on gaining access to the Safer, likening it to the devastating explosion that had occurred just a week earlier in Beirut, Lebanon on 4 August 2020.

October 2020

In October 2020 the Houthis reportedly again reject UN requests for inspections.

November 2020

By November 2020 the Houthis seemingly change their minds and give permission for the UN to come on board early in the first couple of months of 2021 and inspect the latest condition of the Safer.

The United Nations Office for Project Services (UNOPS) releases a Scope of Work (SOW) in November 2020 outlining a condition assessment and light maintenance required to prevent an oil spill, after technical consultations with the Houthis in Sana’a between August and October 2020; the Houthis accept the SOW on 21 November 2020. The SOW allows the UN to be able to start spending donor funds and secure the requisite equipment for the operation. According to the SOW:

There is no basic data available; beyond the information provided by the Sana’a authorities, the only known data of drawings, specifications, reports and procedures are reported to be filed onboard the Tanker

December 2020

On 30 December 2020 the UN releases a Q&A “about the UN mission to the SAFER oil tanker in Yemen”.

2021

January 2021

Outgoing US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo announces on 19 January 2021 (the day before Joe Biden is to be come President) that the Houthis will be designated a “foreign terrorist organisation”, which means that it would be illegal for anyone to knowingly provide them “material support or resources”. Pushback is received from aid officials and former government officials, alarmed at the chilling effect it would have on efforts to provide aid to the Yemeni people, as well as the efforts to deal with the Houthis and resolve the Safer situation.

February 2021

The physical inspection visit scheduled for February 2021 is delayed, with the UN citing on 2 February 2021 a lack of written security guarantees by the Houthi for the inspection, and blames the group for not only creating uncertainty around the timelines but also adding hundreds of thousands of dollars to the operation which up to then had apparently already cost US$3.35 million for the hire of engineers, vessels and equipment.

New US Secretary of State Anthony Blinken, in a widely expected move, reverses the “foreign terrorist organisation” designation of his predecessor effective 16 February 2021.

A year since the previous UN Security Council resolution 2551, the FSO Safer appears in Resolution 2564 adopted on 25 February 2021, but this time much more strongly worded:

Emphasising the environmental and humanitarian risk and the need, without delay, for access of UN officials to inspect and maintain the Safer oil tanker, which is located in the Houthi-controlled North of Yemen, and stressing Houthi responsibility for the situation and for not responding to this major environmental and humanitarian risk, and underscoring the need for the Houthis to urgently facilitate unconditional and safe access for United Nations experts to conduct an assessment and repair mission without further delay, ensuring close cooperation with the United Nations.

With frustration growing over the lack of progress, some calls begin to be made publicly about the need for military intervention to resolve the crisis. In a 10 February 2021 article in The National, it is reported that long-time advocates for the FSO Safer, Dr. Ian Ralby from the maritime security consultancy I.R. Consilium as well as Sir Alan Duncan (a former UK minister and envoy to Yemen), are proposing more direct measures to resolve the looming crisis:

The US and UK should work with the UN Security Council to push for authorisation for a military operation under Chapter 7 of the UN Charter.

Engineers, backed up by military personnel, would demine the water around the Safer, board the ship and drain it of its contents; they said this would take around a month. The Safer would then be sent off to be scrapped.

Ralby was advising the UK government regarding the Safer and Duncan said he would take up the matter with Boris Johnson, UK Prime Minister at the time.

The next month, Ralby (also a Nonresident Senior Fellow at the Atlantic Council Global Energy Center) and two work colleagues, Rohini Ralby and Dr. David Soud, expand on the proposal in an op-ed for the Atlantic Council.

Suffice to say, their calls are not heeded and did receive some constructive criticism from some quarters that their plan would be counterproductive.

March 2021

Another attempt at an inspection visit of the Safer is supposedly to occur in March 2021; it is delayed indefinitely after that.

June 2021

The UN Security Council is briefed on 3 June 2021 by officials from the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs12:

The UN operational team expresses frustration that while various contingency workshops and plans had been developed by regional stakeholders13, the Houthis continue to drag their feet on allowing actual physical inspections of the Safer.

The Houthis reportedly cite concerns about what the UN would do when actually on board the vessel and their inability to provide details of what repairs are required.

The UN team counter that due to lack of access to the tanker, they are not able to provide the required specifics. Despite a lack of success in the previous 10 days to bridge this gap, they are on standby to act as long as funds are still available; once given the go ahead it would still take several weeks to organise vessels, get together equipment and head off from Djibouti to the Safer.

The Yemeni government accuses the Houthis of playing politics with the Safer to achieve their wider strategic objectives.14

July 2021

In July 2021, Iran reportedly make an offer to the UN to facilitate a ship-to-ship transfer of the oil by sending a floating storage vessel to Ras Isa to offload the oil, with the specifics of what to do with the contents decided at a later stage. According to Ibrahim Alseraji, a Houthi spokesperson and leader of the technical team (“Supervisory Committee for the Implementation of the Urgent Maintenance Agreement and the Comprehensive Evaluation of the Safer Floating Tank”) overseeing the Safer issue, the Houthis had not been communicated with about the offer; in the end it went nowhere.

Also in July 2021, another option to resolve the crisis is floated; it is labelled the “Commercial Option”:

The Fahem Group, a major Yemeni grain trading company headed by Abdullah Mohammed Fahem, sees the major disruption a spill from the Safer would have on their business. They engage with a group called Safe Passage Yemen, “a collection of former diplomats, humanitarian experts, and analysts, mostly based in the U.K.” with an interest in Yemen’s future, plus some British and Dutch diplomats.

Their solution to the enormous costs associated with removing the oil from the Safer is to use the proceeds of any sale of the 1.14 million barrels of oil on board, as well as the potential scrap value of the Safer; while no agreement is reached on what to do with any profit from the operation, the Houthis expect it would go to their administration in Sana’a.

Fahem engages the services of the legendary Dutch marine salvage firm Smit Salvage, whose past operations had included the Ever Given stuck in the Suez Canal four months earlier and the Kursk submarine; Smit would run the salvage operation if the plan ever got up.

On the political enagement side, Fahem Group start to have talks with the Houthis during July 2021. While early signs of success are not clear, it appears a few weeks into the process the Houthis have warmed to the idea. One big stumbling block - which would reoccur when it came to finding funding for any operation - was around the huge potential liability around any kind of operation to save the Safer. A neutral party needed to oversee it; while a little surprising considering their past relationship struggles, the Houthis decide the UN should be such a player.

September 2021

In September 2021, it becomes clear that the groundwork from the Commercial Option is beginning to pay dividends. David Gressly, the UN Resident and Humanitarian Coordinator for Yemen, is instructed by the UN Headquarters in New York to “provide UN system-wide leadership on the FSO Safer and coordinate all efforts to mitigate the threat.” According to a UN press release:

The work builds on the earlier agreement in principle between the DFA [Houthis] and the Fahem Group to have SMIT [Smit Salvage] carry out a ship-to-ship transfer of the oil and clean-up of the tanks and responds to the requests of both SMIT [Smit Salvage] and the DFA [Houthis] that the UN hold the contracts for the work. The UN agreed to this because of the significant environmental and humanitarian impact of any oil spill, an event that must be avoided if at all possible.

This means Gressly is to engage with the Yemeni authorities in Aden, the Houthis in Sana’a, internal UN internal working groups, potential donor countries, ship salvage experts and others.

While Gressly is to lead the project, the UNDP will project manage the emergency plan and be the contract holder with relevant parties, with expected services to include “leasing of the replacement vessel, contracting the vessel crew, and maintenance and insurance of the vessel”.

December 2021

A December 2021 meeting of all the relevant UN Principals is held in New York. The UNDP is instructed to “fast-track a single-source procurement with SMIT Salvage”; due diligence on the firm has been completed.

The UNDP would also need to produce a “full project document with a detailed budget” before they can get funding provided to them by the UN’s Peace Support Facility (PSF). Further from the press release:

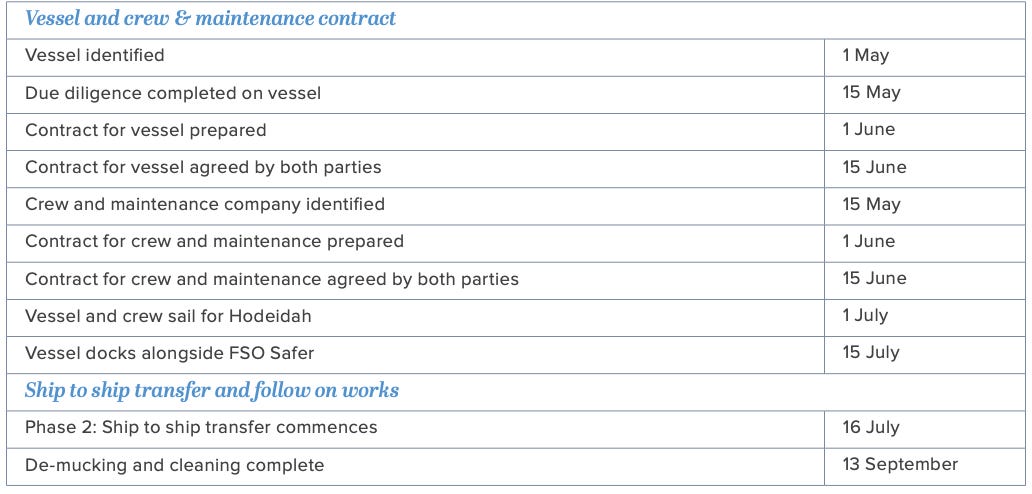

While the final timelines are contingent on the provision of funding, without which contracts cannot be awarded, the aim is to have commenced the contract by 1st June, thus ensuring that the work can be completed before winter winds and sea conditions put additional stress on the mooring system of the FSO Safer and make conditions more dangerous.

2022

January 2022

David Gressly holds talks with Houthi representatives on 29 January 2022 and later announces that they had been “very constructive discussions” and that the Houthis had “agreed in principle on how to move forward with the UN-coordinated proposal”.

February 2022

Early February 2022 David Gressly has “positive discussions” with Yemeni government authorities in Aden who “confirmed that they support the UN-coordinated proposal to shift the million barrels of oil onboard the vessel to another ship”.

On 15 February 2022 an “agreement in principle” is reached between the UN and the Houthis to implement the first part of the rescue plan - the removal of the oil off the Safer - according to the deputy chief for humanitarian affairs for the UN, Martin Griffiths, after earlier discussions between the Houthis and the Yemen Government.

Also during February 2022 (and later in March 2022), the International Maritime Organization (IMO) and UNDP Yemen hold contingency planning workshops with Houthi and Yemeni government officials to strengthen their capacity to respond to any oil spills.

March 2022

On 5 March 2022 a memorandum of understanding is reached between the UN, the Fahem Group and the Houthis, with the key points below:

The UN is to provide a replacement vessel to allow export of the oil currently on the Safer, with a target date of 18 months.

It won’t cost the Houthis any money, but they need to provide “all facilities for the success of the project”.

A temporary tanker to get the oil from the Safer to a temporary vessel (before the permanent tanker is provided) may be required.

The UN will come up with an operational plan.

April 2022

A two-month truce between the two main warring parties commences on 1 April 2022, as announced by UN Special Envoy for Yemen, Hans Grundberg. Since the war began, an estimated 400,000 people have been killed, with a majority as a result of a lack of food, usable water and healthcare.

On 7 April 2022 President Hadi, in exile in Saudi Arabia since 2017, delegates his own power to the eight-member Presidential Leadership Council, which includes the separatist Southern Transitional Council but not the Houthis; it is done reportedly under pressure from Saudi Arabia.15

The UN Secretary-General António Guterres sends a letter to the President16 of the UN Security Council on 8 April 2022, recapping the recent developments to try and get a resolution to the Safer issue, the operational plan as well as the need to raise funds, concluding with:

I wish to reiterate to the members of the Security Council the urgent need to address this potential regional disaster before it strikes and my endorsement of the operation plan to address the Safer oil tanker in the manner envisaged.

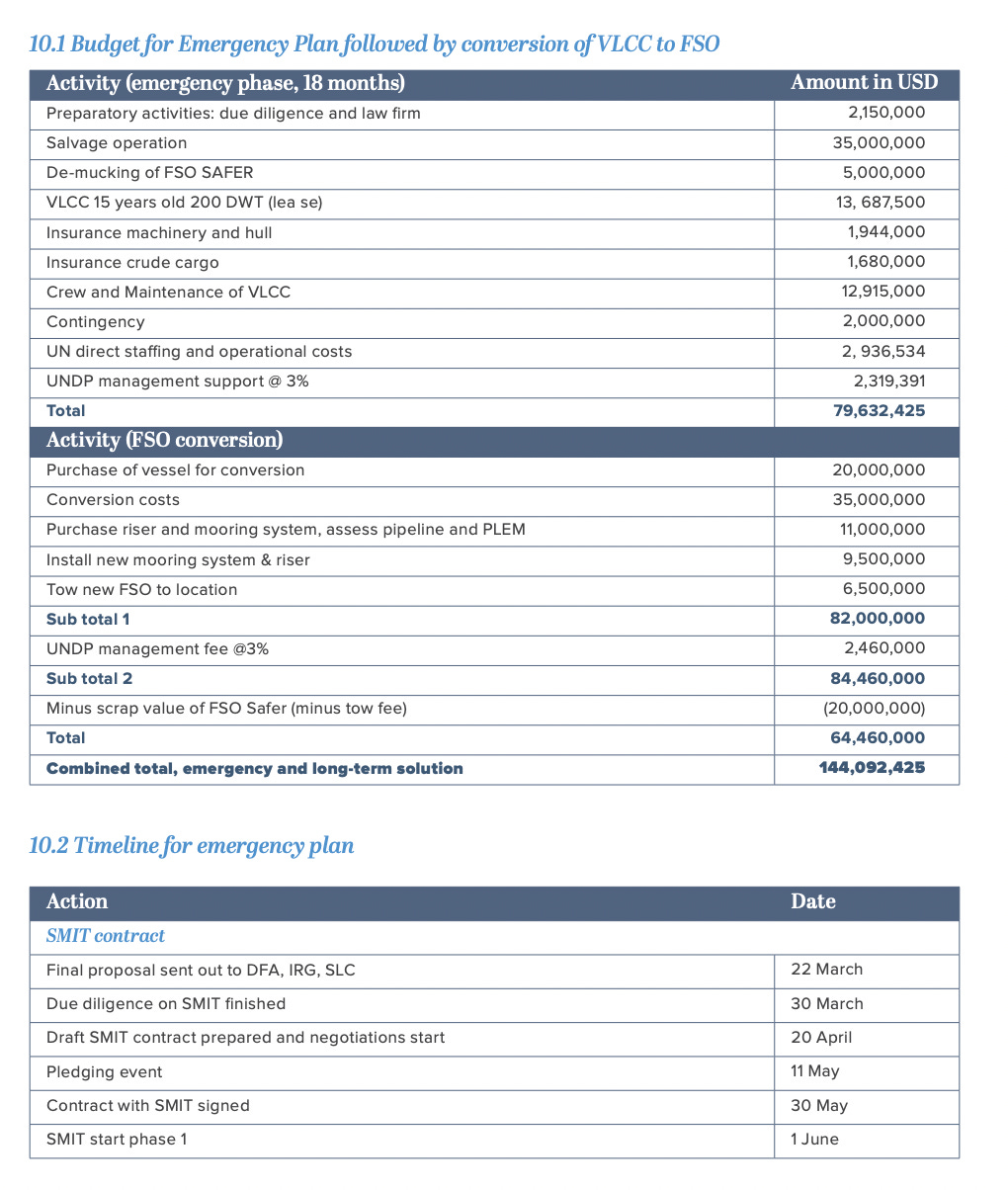

In April 2022 the UN releases the Operational plan for the rescue of the Safer, including the budget and projected timelines.

High level summary of the Plan:

Stage One/Emergency Phase (4 months) - Due to the urgency of getting the oil off the Safer, a temporary suitable vessel like a VLCC (Very Large Crude Carrier) to be leased to allow the transfer of oil onto a more stable vessel. A specialist salvage company would first inspect and prepare the Safer for the oil transfer and then conduct the operation itself once the temporary vessel was in place. The latter would then remain until a more permanent vessel was secured and in position. The Safer would then be transported elsewhere to be sold as scrap, to recoup some of the costs of the operation.

Stage Two (18 months) - The end goal is the provision of a permanent vessel or solution to replace the oil export facilities previously provided by the Safer. This would take the form of either:

a replacement FSO (which would require modification of a vessel at an available dry dock yard - with an expected timeline of 18 months), or

the installation of a CALM (catenary anchor leg mooring) Buoy system, which could be used in one of the following ways:

with a VLCC semi-permanently moored to it and acting as a storage facility

using the VLCC in a. above in conjunction with an onshore storage facility (either at the time or at a later stage)

instead of using a VLCC, the CALM buoy would be linked directly to an onshore facility

The role of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) is to support the UN Resident and Humanitarian Coordinator for Yemen, David Gressly, through their country office and Peace Support Facility, when it came to fundraising discussions with member states and other donors.

Smit Salvage, who undertook a lot of the technical overview of the operational plan, were also identified as the operator who would undertake the transfer of the oil off the Safer. The legendary Dutch ship salvage company, who amongst other high profile rescues were responsible for getting the Ever Given unstuck from the Suez Canal in April 2021, releases a video showing what that process would look like:

May 2022

On 11 May 2022, a pledging conference is co-hosted by the Netherlands and the UN in order to raise funds from member nations towards the two-stage plan, with Stage One being the immediate priority.

The target is ~US$80 million for Stage One and then ~US$64 million for Stage Two). After the event, US$40 million is raised, as follows:

US$7 million of existing UN funds was already available prior to the pledging event

~US$33 million is pledged by various donor countries including:

US$10 million - Germany

US$7.5 million - The Netherlands

US$5 million - United Kingdom (UK)

~US$11 million - across the EU, Finland, France, Luxembourg, Norway, Qatar, Sweden and Switzerland.

June 2022

2 June 2022 sees another two-month extension of the truce.

On 8 June 2022 the United States pledges US$10 million to the rescue plan, with Saudi Arabia following suit on 12 June 2022 also with US$10 million.

On 13 June 2022, David Gressly holds an online hosted by the think-tank Sana’a Center for Strategic Studies, in which he:

announces the launch the next day of a crowdfunding campaign to try and bridge a US$20 million gap in the funds required for Stage One or emergency operation,

emphasises that all of the funds for Stage One need to be raised before the mission can start due to the dependency of having a replacement vessel ready to take on the oil, and

engages in a Q&A after his talk and gets some pointed questions about delays to the emergency plan, why all of the funds were needed before the operation could start and the perceived benefits that the Houthis were getting out of it.

On 14 June 2022, the crowdfunding campaign is officially launched with a link provided for donations as well as a social media campaign aiming to raise attention and US$5 million in funds from the public by the end of the month. The hope is to start the operation 1 July 2022; this does not occur.

July 2022

The UK pledges an additional $US2.4 million on 18 July 2022 to the fundraising effort.

August 2022

2 August 2022 sees a second extension of the UN truce for another two months.

On 25 August 2022 the first private corporation to assist with the fundraising driver becomes the HSA Group – Yemen, who pledge US$1.2 million

September 2022

Canada pledges US$2 million on 6 September 2022 (and pays up a day later) with the Netherlands adding an additional US$7.5 million on 17 September 2022 (on top of their previous US$7.5 million).

On 21 September 2022, at a “High-level FSO Safer Side Event” co-hosted by the Netherlands, the United States and Germany during UN General Assembly Week, it is announced that a now reduced (due to operational efficiencies) Stage One budget target of US$75 million has been reached. Germany adds an extra US$2 million (to their previous US$10 million) to the tally while Finland throws in US$1 million. The Crowdfunding balance at the time is about US$0.2 million.

While the achievement of the US$75 milllion milestone is a fantastic achievement, David Gressly and the UN make it clear that the funds need to be converted into cash in UN bank accounts before the operation can proceed. As of 18 September 2022, only US$59 million has been converted or is in the process of being converted. A waiting game will have to proceed.

It is also revealed at the event that the Stage Two budget has been reduced from US$64 million to US$38 million as a result of the Houthis and the Yemeni government agreeing on a double-hulled VLCC tanker tethered to a CALM-buoy system as the solution, rather than a standalone FSO being procured and converted.

October 2022

On 2 October 2022, the deadline for a third extension of the UN-sponsored truce between the main warring parties passes without a deal being struck. During the six months of the truce, civilian deaths decreased by 60% and displacement by half, with some semblance of normal activity possible, such as an increase in food imports via the port of Hodeidah; there are, however, still incidents of political violence between April and October. An anxious period of waiting begins.

In late October 2022, a report from Arab News provides a little more clarity on the Safer situation.

Cash funding has been secured, with pledges turned into actual funds.

Contracts are yet to be finalised with the salvage company (Smit Salvage).

Procurement of the temporary vessel to hold the transfer of oil is still pending.

Completion of a detailed operational plan is still required and stipulated by the Houthis as a pre-requisite before the go-ahead for further work on the Safer. Smit Salvage is expected to conduct a physical examination of the Safer in November 2022 before this could be finalised.

A timetable is only to be released after completion of the detailed operational plan.

Transfer of oil is only realistically expected in 2023 due to all the of the above dependencies above, as well as the preparatory and repair work required on the Safer.

2023

January 2023

On 17 January 2023, the UN provides an update to the media to the effect that the search for the temporary vessel to initially take on board the oil from the Safer is proving harder to achieve than initially thought. The initial plan was for a vessel to be leased while the search for a more permanent solution was undertaken. But it turned out that trying to get an appropriate VLCC vessel to lease or purchase is now a lot more expensive, thanks (but no thanks) to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February of 2022. Selected comments from UN Deputy Spokesperson Farhan Haq are as follows:

With more than $73 million of the pledges disbursed, the UN has been able to begin essential preparatory work. All of the technical expertise is in place to undertake the procurement for the complex operation. This includes a marine management consultancy firm, maritime legal firm, insurance and ship brokers and oil spill experts. The contracting of the salvage company that will carry out the emergency operation is at an advanced stage. However, the key challenge at present is procurement of a very large crude carrier. The UN cannot begin the emergency operation until it is certain that a safe crude carrier will be in place to take on the oil. The UN is working expeditiously with a maritime broker and other partners to find a workable solution and remains confident the work can begin in the coming months….. the availability of those ships has decreased in the past six months, basically due to events having to do with the war in Ukraine. So, just as we were gearing up for operations, the cost to both lease and purchase this type of a vessel increased. So, a very large crude carrier now costs at about 50 per cent more than what's budgeted in the original plan. So, we have some additional expenses and it's a little bit harder finding the right ships, but we're proceeding with the work.

Richard Meade, editor of the venerable shipping industry journal Lloyds List, publishes an open appeal on 27 January 2023 for any shipowners to come forward and assist with the procurement of a suitable VLCC to take on the oil, whether at below cost or with the provision of funds:

Any owner even considering joining the effort needs to know upfront that they are entering an unprecedented and difficult situation. But extraordinary is what the shipping industry is routinely able to deliver. If you feel able to step forward, we will happily furnish the introductions.

February 2023

On 28 February 2023, Richard Meade previews that progress on getting a suitable VLCC might be nearing the end:

March 2023

The UN announces on 9 March 2023 that a tanker has now been indeed found. The UNDP will be purchasing an unnamed VLCC owned by Belgian tanker company Euronav at a reported $US55 million, US$20 million more than was originally budgeted. Further:

The VLCC is in dry dock in Asia for regular maintenance and some required modifications, and is expected to arrive in Ras Isa in early May 2023.

As of 7 March 2023, $US95 million has been pledged and US$75 million has been received (cash).

The revised Emergency Phase budget is now a total of US$129 million after the purchase of the vessel to store the oil, driven by the higher cost of tankers; it was also originally intended to be leased.

Therefore, the UN is now $US34 million short of their funding target and needs that to be dramatically closed to allow the operation to commence in the second quarter of 2023.

To partly assist, the crowdfunding campaign is officially relaunched, with a target of $US500,000 this time around.

Here we go again.

Euronav confirm on 10 March 2023 the purchase of a “suitable vessel” and outline their involvement in the operation:

Operate the vessel during the oil transfer and for “several months” afterwards as well.

Provide “dedicated support from Euronav for at least nine months”.

There is some speculation online in the weeks after the announcement about which exact existing tanker has been purchased by the UNDP:

After excluding all VLCC’s not situated near China (as reports indicated it would be in dry dock there), on 13 March 2023 Insurance Marine News lists out all of the available Euronav vessels:

Vessels in China include the 2016-built, Belgium-flagged Aegean (IMO 9732553), the 2016-built Liberia-flagged Desirade (IMO 9723095), 2015-built, France-flagged Dia (IMO 9723071), 2021-built, Belgium-flagged Diodorus (IMO 9877779), 2016-built, France-flagged Donoussa (IMO 9723083), 2017-built, Liberia-flagged Hatteras (IMO 9730098), and finally, the 2008-built, Liberia-flagged Nautica (IMO 9323948), which is by some stretch the oldest of the Euronav vessels in the region.

Ahmed Kulaib, SEPOC’s General Manager17 in 2014 when the Houthis took over the region, looked up ship tracking data and posted on Twitter on 20 March 2023 that the most likely vessel was the Nautica. In his view, having a tanker 15 years old reduced its chances of being sold as a going vessel later, even if it could withstand the harsh environs at Ras Isa; for example, harbours in Abu Dhabi and India only allowed entry of tankers with a maximum age of 20 and 25 years, respectively; in addition, an older vessel such as this could deteriorate and potentially become a new Safer in the future.

April 2023

On 5 April 2023, Achim Steiner, the Administrator of the United Nations Development Programme, announces that the previously unnamed Nautica tanker is close to departing for the Red Sea in preparation for the operation to transfer the oil from the Safer. So what do we know about it?

15 year’s old, built in China, with 307,000 DWT and is 306 metres long

Began service in 2008 as the “Maersk Nautica”

Acquired by Euronav in 2014 and currently registered in Liberia

In dry dock in Zhoushan, China since early March 2023, with regular maintenance and modifications just been undertaken for the Safer operation

The Nautica sets sail on 6 April 2023 from Zhoushan on its way to Yemen, with its first scheduled stop in Singapore on 15 April 2023. However, a funding gap still exists; with US$95 million of firm pledges and a total (now increased) budget for the first phase (the emergency operation) of US$129 million, US$34 million is still required.

On 15 April 2023 the Nautica arrives in Singapore with a planned stop of a few days. In an interview with the Straits Times, UNDP Administrator Achim Steiner updates that US$29m is now outstanding to fund all of the emergency operation, with the actual salvage stage currently unfunded; “emergency bridging financing solutions" are being looked at. He also flagged that a UK/Netherlands-hosted donor pledging meeting was to be held 4 May to try and close the gap.

UK Minister of State (Development & Africa) Andrew Mitchell confirms on 18 April 2023 that he and Dutch Minister for Foreign Trade and Development Cooperation Liesje Schreinemacher will co-host a pledging conference to try and close the US$29m funding gap. Also on that day the Nautica departs from Singapore to Yemen via the Malacca Straits.

On 20 April 2023, CEO Peter Berdowski of Boskalis, SMIT Salvage’s parent company, announces that a signed agreement has been finally reached with the UNDP to undertake the rescue operation in line with the Operational Plan released the previous year. A day later on 21 April 2023, their vessel Ndeavor leaves Rotterdam on a three-week journey to Djibouti, where it will make final preparations before heading for Yemen and the Safer. The operation is expected to take two months once it arrives, with the endpoint seeing the Safer being transported to a green yard for scrapping.

Also on 21 April 2023, the UN’s International Maritime Organisation sends out a notice to any member states “seeking contributions of used or near end-of-life spill response equipment that can be transported to the region within weeks”.

May 2023

The UK and the Netherlands co-host a virtual event on 4 May 2023 nearly a year after the first pledging event was held. While the 2022 fundraiser resulted in US$33 million of pledges (with more following in the weeks afterward), this one raised only a total of US$7.6 million, including US$5.6m million in new funds:

Pledges were announced by “Egypt, France, Italy, Luxembourg, Malta, Norway, Republic of Korea, United Kingdom and private company Octavia Energy”.

Octavia Energy and their subsidiary Calvalley Petroleum, active in Yemen through their oil extraction and exploration activities, give a joint donation of US$0.3 million.

US$23.8 million is still required for the remainder of the first stage (the oil transfer), while an additional $US19 million will also need to be raised for the second stage involving the installation of a catenary anchor leg mooring buoy tethered to the Nautica and the towing of the Safer to a green yard for scrapping.

The Nautica, after departing China in April 2023, arrives in Djibouti on 7 May 2023 where it will await SMIT Salvage’s inspection and preparatory work on the Safer once the Dutch firm’s vessel Ndeavor has made its own journey from Rotterdam to Yemen.

SMIT Salvage’s Ndeavor ship reaches Djibouti on 23 May 2023; the Egyptian authorities waive any transit fees for its passage through the Suez Canal as their contribution to the UN mission, which can usually be hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Negotiations are completed very late on 26 May 2023 between the UNDP, the insurance broker Howden and a consortium of underwriters on a package of insurance policies for the next stages of the emergency operation.

The progress on the insurance front allows SMIT Salvage’s Ndeavor to depart Djibouti on 29 May 2023 along with 40 salvage experts and support staff.

The Ndeavor arrives nearby the Safer on 30 May 2023 ready to commence inspections and injection of inert gas, with activities anticipated to include the following:

Taking a variety of gas measurements inside the Safer to ensure it is “safe to access” for the salvage.

Visual assessments of key areas such as the pump and engine rooms.

The loading of mobile inert gas generators to fill the cargo tanks with inert gas.

Inspection of the stored oil in the tanks and the condition of the cargo and inert gas lines, valves and manifolds to determine if the salvage plan needs to be tweaked.

Also an inspection of the condition of the mooring arrangements as well as underwater inspections where required.

Also on 30 May 2023, the UN releases new fundraising numbers:

US$114 million now received

US$29 million still required (US$14 million for emergency operation incl. oil transfer and cleanup of Safer; US$15 million for CALM-buoy and scrapping of Safer final stage)

On 31 May 2023, the Ndeavor arrives near the FSO Safer which allows members of the SMIT crew to board for the first time via a swinging crane to conduct initial inspections (the Ndeavor cannot actually berth alongside immediately):

Gas measurements are taken in and around the Safer to assess the presence of toxic gas. The ship is declared “safe to access”.

Mobile inert gas generators are loaded onto the Safer.

Inspections of the Safer, its deck machinery and assessments of its structural hull commence.

Based on a project outline released by Boskalis, below are the original anticipated deadlines from the Ndeavor first arriving and allowing team members to board for initial inspections:

Phase 1: 31 May - 16 June 2023

Arrival alongside by salvage team on SMIT’s Ndeavor

Inspection of Safer by SMIT team

Stabilisation of oil storage tanks including pumping in of inert gases

Phase 2: Assumed 16 June 2023 (1 day travel)

Replacement vessel Nautica gets go-ahead to travel from Djibouti

Comes alongside Safer and moored

Safety precautions including installation of oil booms in seawater

Phase 3: 17 June - 5 July 2023

Ship-to-ship transfer of oil

Phase 4: 7 July - 23 July 2023

Cleaning of thick sludge and scrubbing of storage tanks

Dirty water transferred to Nautica

June 2023

Below is a summary of various known inspection and inspection-related steps undertaken by the SMIT team during the period 1-14 June 2023. [These will get updated as more information comes to hand]:

The Ndeavor berths alongside the Safer and initial inspections continue.

Inert gas generators and ship-to-ship transfer equipment are transferred onto the Safer.

Inspection of the manifold on board commences.

A mobile fixed staircase is built to make access to the Safer easier and safer, rather than being moved onboard by a crane.

Pumping in of inert gas and work on manifold commences.

It is announced on 12 June 2023 that coverage had been binded on insurance policies for the upcoming operations, including for the ship-to-ship oil transfer and for the replacement tanker Nautica; negotiations on these had been completed on 26 May. This basically means that they are now in force.

On 21 June 2023, Oil Spill Response Limited (OSRL), an oil and energy-owned company which assists with oil spill prevention and response services, announces that the UNDP, who are project managing the Safer operation, have become “associate members” which means that:

The UNDP has access to OSRL who are on standby with aircraft, dispersants & expert support for the oil transfer operation - if required (i.e. a spill occurs).

The OSRL have "carried out a comprehensive risk analysis study on the potential land, marine, and air operations.

Boskalis, SMIT’s parent company, provide an update on 27 June 2023:

Over past 2 weeks, "further good progress" has been made on oil transfer preparation.

Recent work has focused on inspecting & reinstating equipment on board, including winches for mooring & stripping pumps for remnants of oil.

Underwater inspection of the hull by professional divers has now been done.

Two tugboats arrived on site to assist with berthing of replacement Nautica when it arrives.

Oil booms are to be installed as a precaution for oil transfer.

July 2023

At the monthly UN Security Council update on Yemen on 10 July 2023, David Gressly announces that only that day had the go ahead been given by the Houthis for the replacement VLCC Nautica to depart Djibouti for Yemen. Considering the de facto authorities in the north of the country had agreed to the operational plan, this suggests some political wrangling has been going on behind the scenes - and not for the first time.

On 15 July 2023, David Gressly confirms that the Nautica has now departed Djibouti. (It arrives later that day.)

On 17 July 2023 a ceremony is held where the UN hands over control of the Nautica to the national oil company SEPOC onboard the replacement vessel. This is a contentious point because this effectively means that it belongs to the Houthis who control the port where the Safer and now Nautica are located. The Houthis then also rename it the Yemen.

From an operational perspective, to avoid the two large tankers from making contact with each other during the ship-to-ship transfer, on 20 July 2023 large Yokohama pneumatic fenders are installed off the Yemen to create sufficient space between the two vessels. In the next couple of days, tugboats then manoeuvre the Yemen next to the Safer in preparation for the ship-to-ship transfer of oil.

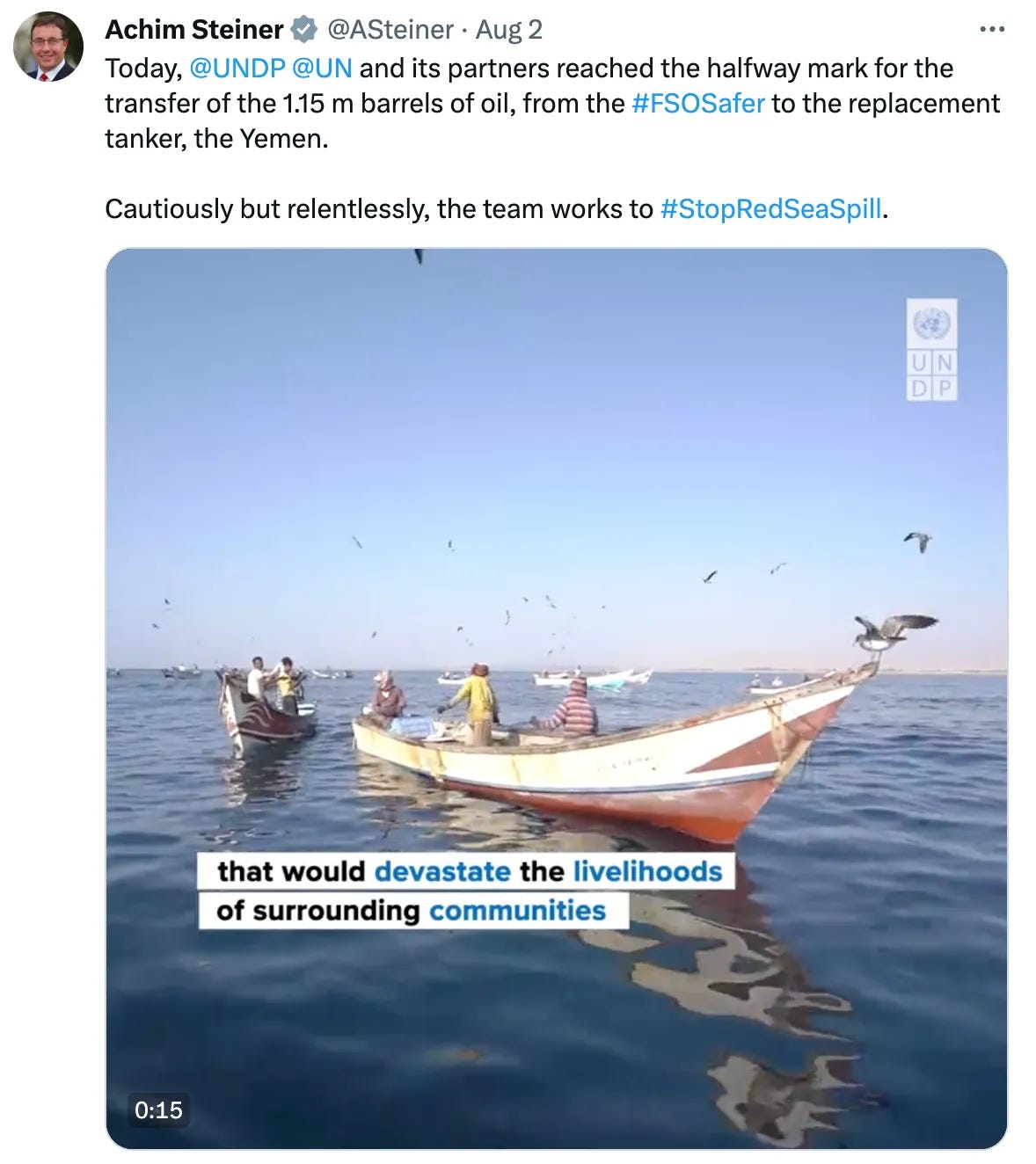

At 10.45 Yemen time on Tuesday, 25 July 2023, it is announced that the actual pumping of oil has begun. It is expected to take between two to three weeks. SMIT Salvage will lower hydraulic pumps into the storage tanks while a chemist monitored for safe levels of inert gases.

The UN also provides an update on some other Safer-related matters:

By September a catenary anchor leg mooring (CALM) buoy should be delivered and installed, to which the replacement Yemen would be tethered allowing it to connect to a pipeline for oil transport.

Regarding the sale of the oil being transferred between ships - a topic which had effectively been parked for a later stage when agreement had been reached in 2022 for the UN Operational Plan to go ahead - UNDP Administrator Achim Steiner said the sale “is indeed on the horizon” and indicated that talks with both sides in Yemen had been held. Samples of the oil in question had apparently been sent to a laboratory for testing of its quality and viability for sale.

On 28 July 2023 (Day 4 of the oil transfer operation), Boskalis posts that the “oil transfer is progressing well” and provides some video footage showing the preparation of the Yemen for the oil transfer (including the installation and lowering off its side of giant pneumatic fenders to prevent the two ships from touching each other), its mooring alongside the Safer with the assistance of tugboats, the lowering of an oil boom into the water around the vessels in case of a spill, the insertion of hydraulic pumps into the storage tanks, and the start of the pumping of the oil from the Safer to the Yemen. The UN advises that 223,000 barrels has been transferred so far (around 20% of the total so far).

On 30 July 2023 (Day 6), the UNDP advises that two central tanks are now emptied.

UNDP Administrator Achim Steiner advises on 31 July (Day 7) that over 360,000 barrels or around one-third (33%) has been transferred.

August 2023

The halfway mark is reached on 2 August 2023 (Day 9), of around 570,000 barrels transferred.

60% (680,000 barrels) is reached on 3 August 2023 (Day 10)

71% (824,179 barrels) have been transferred by 6 August 2023 (Day 13)

80% (~ 900,000 barrels) is now on board the Yemen as at 8 August 2023 (Day 15).

By 9am on 9 August 2023, 1,105,000 barrels or 96% has been pumped out.

The big moment then arrives with the news that at 18:00 local time on Friday, 11 August 2023, the main transfer of the oil is now complete. This amounts to about 98% of the total oil, with the remaining sludge to be dealt with in the next stage where the storage tanks will be cleaned and scrubbed; residual dirty water will then be transferred to the Yemen.

SMIT Salvage’s parent company, Boskalis, announce that the final stage of their operation has been completed on 28 August 2023, namely the cleaning of the tanks of the Safer (demucking of the oil sludge, scrubbing and presuambly transfer of dirty water onto the Yemen) as well as assisting with the mooring of the Yemen to a location nearby the Safer. The next day on 29 August 2023, their support vessel Ndeavor left Yemen and arrived in Djibouti the next day; the salvage crew was to disembark and the Ndeavor was then to return back to Rotterdam.

Appendix: Pledges received by the UN as at 2 January 2024 [requires updating]

The below is based on publicly available information, but does contain gaps requiring confirmation.18

When it was active out on the sea, it reportedly took it about 15 minutes from full speed to stopping, and required about 3.2 kilometres of clear water.

The Southern Movement emerged in 2007 with new calls for secession. A later offshoot backed by the United Arab Emirates, The Southern Transitional Council, was founded in 2017. While not representative of all the southern factions, it is a dominant group with powerful backers.

Other points of contention are President Saleh’s support for the US during the 2003 Iraq War and the influence of Saudi-backed Wahhabi ideas.

On 21 November 2005, YEPC filed an arbitration claim with the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC), with financial claims and counter-claims being presented by both parties. In October 2008 the ICC ruled against YEPC and in favour of the Yemeni government; while the latter were required to pay the legal costs of the arbitration and were not to receive their counterclaimed compensation, they did get to keep the proceeds of any oil extracted from 2005 onwards which would have been worth several billions of dollars.

Ed Caesar notes that: “[Saleh] was astonishingly corrupt. A U.N. panel has estimated that while he was in power he acquired as much as sixty billion dollars in personal wealth. He also appears to have played a double game with the West: he officially aligned himself with the war on terror while tacitly providing support for proscribed Islamist organizations, to keep foreign aid flowing in.”

This was made up of a chief engineer, an electrician, two mechanics, a cook, and a cleaner.

He would continue to brief the Council monthly on any updates until being replaced in his position by Martin Griffiths in May 2021.

Ras Isa is then removed in 2017 from the list of ports allowed to be given clearance.

Also during the 2020/2021 period, briefing papers, modelling studies and impact assessments regarding scenarios surrounding the Safer spilling its oil cargo are published, including but not limited to:

The non-profit analysis group ACAPS, in conjunction with Riskaware and another non-profit Satellite Applications Catapult, release modelling assessments, funded by the UK Government, of a spill and its impact if it were to occur during the period October-December 2020 and later April-June 2021. (A further update is released in April 2022.)

An article by Benjamin Q. Huynh et al is published in Nature in October 2021 with the title “Public health impacts of an imminent Red Sea oil spill”.

Greenpeace release a briefing paper in December 2021 entitled “FSO Safer: A Shipwreck in Slow Motion” outlining in detail the “humanitarian, economic

and environmental impacts of an oil disaster in the making in the Red Sea”.

It is also stated that the “Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator briefed the Council 23 times on the Safer, including in a meeting dedicated to the issue in July 2020.”

From the UN briefing: This includes “the Regional Organization for the Conservation of the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden, Yemeni authorities and International Maritime Organization (IMO)” who “have developed regional and national contingency plans, as well as contracted a private company to provide updates in the event of a spill. These efforts have been paired with a series of capacity‑building workshops on responses at the regional and national levels, which involve training on the use of spill‑response equipment and on the use of dispersants.”

The Houthis have rejected this charge and provided their own counter-narratives:

They stated they were serious about resolving the issue, but would not do so at any cost and wanted to “maintain the economic value” of the current set up around Hodeidah, including the oil on the Safer itself. With control over the Marib pipeline (although it seems to be in a state of disrepair) and some kind of facility like the Safer (or a replacement) in place, it would just take a victory in their quest to seize control over the Marib oil fields, to potentially be able to export oil.

They have claimed that the UN have reneged on certain promises and “not been transparent”.

There seems to be general distrust of the UN. For example, according to reporting by Ed Caesar, the UN had received a request by the Houthis that their own divers accompany those of the UN when it came to making inspections. On another occasion they issued new demands regarding “logistics and security arrangements” prior to a scheduled inspection in February 2021. The Houthis rejected UN claims about them making such additional demands and not issuing entry visas, counter-claiming that the UN was to blame.

There was resentment about the blockade of Hodeidah by the Saudi-led coalition, blaming this for preventing workers being able to access the Safer to carry out repairs. This animosity also manifested itself when the scheduled inspection in August 2019 was called off over a dispute over the inspection of ships away from Hodeidah before being allowed to enter the port.

Different priorities seemed to be in play about the extent of maintenance required upon the primary inspections, with the Houthis seeming to want more extensive repairs so that the Safer could be made operational again; the UN was more focused on getting the Safer ready for the transfer of oil off the vessel.

In June 2020, they insisted that the Safer situation must be seen as part of a wider peace package which they had proposed.

They have accused the world about being more concerned with the environment than the people of Yemen.

A response from the UN Security Council President is sent back two weeks later, acknowledging the issues surrounding the Safer.

He started as a loading master with the Hunt Oil Company in 1988 when they bought the Safer and moved up the ranks, working very closely with the Safer.

Items still requiring confirmation:

The fundraising event co-hosted by the Netherlands and the UK on 4 May 2023 was said to have raised ~US$7.6m which consisted of US$5.6m of new funding, but that the UK had also released a further ~US$3m. It is unclear if the UK’s US$3m was included in the US$5.6m - the total for those combined then have been left totalling US$7.6m until further clarified.

The contribution amounts from the Trafigura Foundation (US$1m) and the International Association of Oil and Gas Producers (US$10m) were confirmed by David Gressly but it is not clear when they were exactly made.

There is nearly US$11.4m of unaccounted for pledged funds - this will be confirmed and updated when possible.