FSO Safer: Ahmed Kulaib disagrees strongly on the UN Plan

The former SEPOC General Manager thinks it is an expensive, temporary solution

He has been there since the beginning

Ahmed Kulaib has a long history with the FSO Safer.

He joined Hunt Company in 1988 as a loading master, which was the same year the Texan oil exploration company saw delivery of the FSO Safer as a floating oil storage and offloading vessel to export Yemen’s recently discovered oil in the Marib region.

With only a 15-year licence to extract oil and an estimated $100 million cost to build an onshore terminal which would take years, they purchased the Esso Japan tanker (which had been retired in Norway) and had it converted into its new purpose for a tenth of the cost; it was renamed the Safer.

According to Kulaib, who would eventually rise up to become General Manager of Yemen’s national oil company SEPOC (Safer Exploration & Production Operations Company), discussions about building an alternative permanent, onshore terminal began in the 1990s.

As reported by Ed Caesar in the New Yorker, when Hunt was granted a five-year extension on their oil extraction deal in 2000, a committee was set up by the government to plan an onshore storage facility. However, it ended up going nowhere.

Abdulwahed Alobaly, an accountant who used to work for SEPOC, the state-owned oil company, told me that the project’s budget was about a billion dollars—a wildly excessive sum. Not a brick was laid. Alobaly, who fled Yemen four years ago, told me that he suspected “huge corruption.”

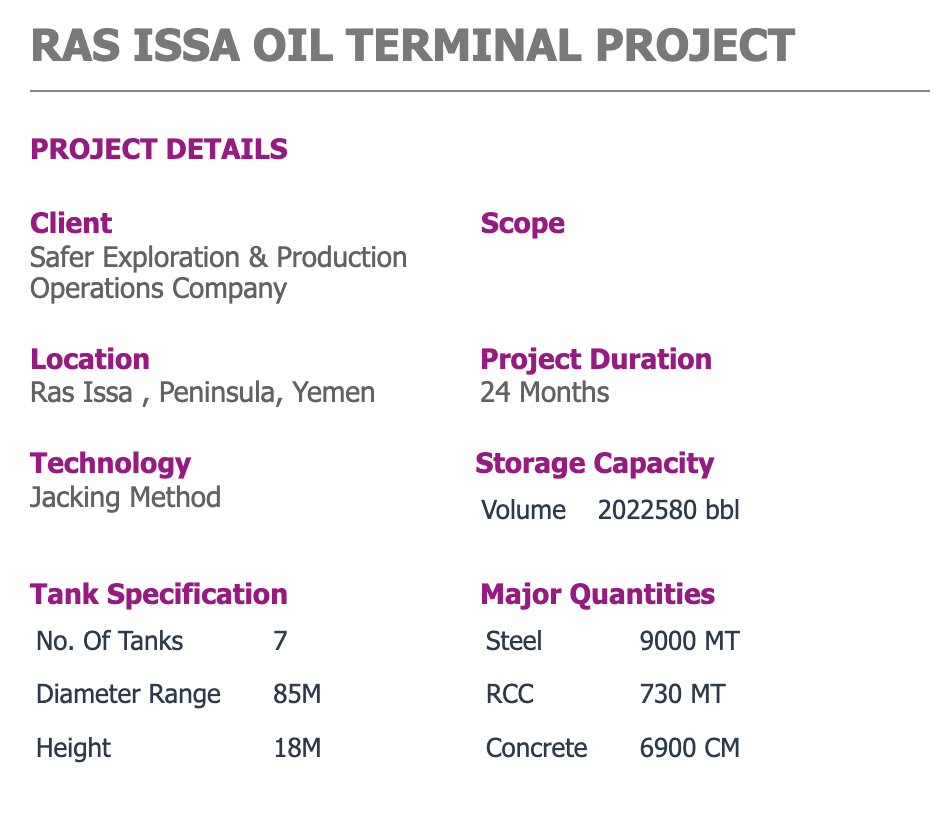

Years later, the project was handed over to SEPOC, who in 2005 had taken over the operation of the FSO Safer after Hunt’s attempt at an extension was rejected.

Work on the project was mainly to be conducted by the Bulk Storage Terminals company Chemitech for the onshore terminal portion, while offshore work would be done by the offshore mooring system firm SOFEC. The total cost was $160 million, with $120 million and $40 million for the onshore and offshore aspects, respectively.

Work began in 2013 as Ed Caesar describes:

Hundreds of Yemeni and international contractors set up camp at Ras Issa and began constructing three enormous vats for storing crude oil. From the site, the workers could see the Safer floating on the horizon. Sameer Bawa, a director at ChemieTech, remembers discussing the poor state of the ship with crew members who came onshore. “That was what everyone was talking about—that it may sink at any time,” Bawa recalled.

The new oil terminal was half built when Yemen’s capital, Sana’a, was overtaken by the Houthis.

The Houthis took control of the port of Ras Isa in March 2015, confiscated SEPOC’s budget, which left a skeleton crew to try and maintain a decaying tanker with what limited resources they had; the rest is history. Ahmed Kulaib left Yemen a couple of years later, “[e]xasperated by the corruption and chaos that ensued”.

Ahmed Kulaib’s critiques of the UN Operation

The core of his critique - which he has outlined on Twitter since joining the platform in January 2023 - ultimately goes back to what the intention of the FSO Safer was in the first place, namely a temporary solution to allow the export of oil from the Marib oil fields east of the capital Sana’a, until an onshore terminal could be built. (According to Kulaib, from 1987 through to March 2015 when exports ceased, some 1,328,050,910 oil barrels or on average 130,000 per day went through the Safer.)

A replacement vessel would face a harsh Red Sea environment

When the UN announced on 9 March 2023 that a replacement VLCC tanker had been purchased at great cost due to the knock-on effect of the invasion of Ukraine by Russia (and the non-availability of an interim leasable vessel), Kulaib outlined on Twitter why he thought this was not a good idea.

While the Safer is old and single-hulled, it is reinforced with thick steel and has additional cathodic protection not matched by more modern tankers which, while double-hulled, are not as thick.

The environment in the Ras Isa area is hostile in a number of ways which contribute to corrosion: extreme salinity, high temperatures up to 50 degrees celsius, dense sand and salty water.

The Safer’s ballast tanks were modified to allow oil to be used in them, instead of seawater which is corrosive and used in more modern ships.

The Safer had modifications which enabled safer and more effective transfer of oil due to at times difficult conditions at sea. Its Single Point Mooring (SPM) stabilised the ship and allowed it to turn in a full circle depending on the direction of the wind. Its Side-By-Side (SBS) and Tandem loading systems also allowed for flexible oil-offloading, the latter meaning rear-loading was possible particularly during half of the year when side-loading becomes more difficult due to weather conditions.

With the above challenges facing any replacement tanker, Kulaib raised the question of operational budget being available to manage these risks, as well as the sourcing of workers (including foreign ones) to prevent a new Safer situation from occurring.

Having a permanent onshore processing and storage facility in operation, rather than a floating solution which has got Yemen into the situation it is in now, would have been more desirable and a lot more cost effective.

The replacement vessel is already 15-years-old

The UNDP did not announce at the time the identity of the Euronav tanker it had purchased, but speculation narrowed it down to a few contenders, with Kulaib later posting that the most likely candidate appeared to be the Nautica; he was not pleased.

His main issue was that at 15-years-old, the Nautica was already well on its way to being too old:

If a future sale of the tanker was desired, its chances of being snapped up were diminished because of its age and perceived usefulness to any prospective purchaser; it may just end up being sold as scrap.

He said that “[m]ost countries in the world prevent tankers over 20 years old from entering their ports in order to preserve the safety of their environment and ports”, and went on to cite the example of Abu Dhabi and India (although noting the latter has a 25 year limit).

With modern ships being more vulnerable to corrosion, having a 15-year-old tanker meant that its useful life was already well on its way to being reached.

The priority should have been to sell the oil, not spend a lot of money

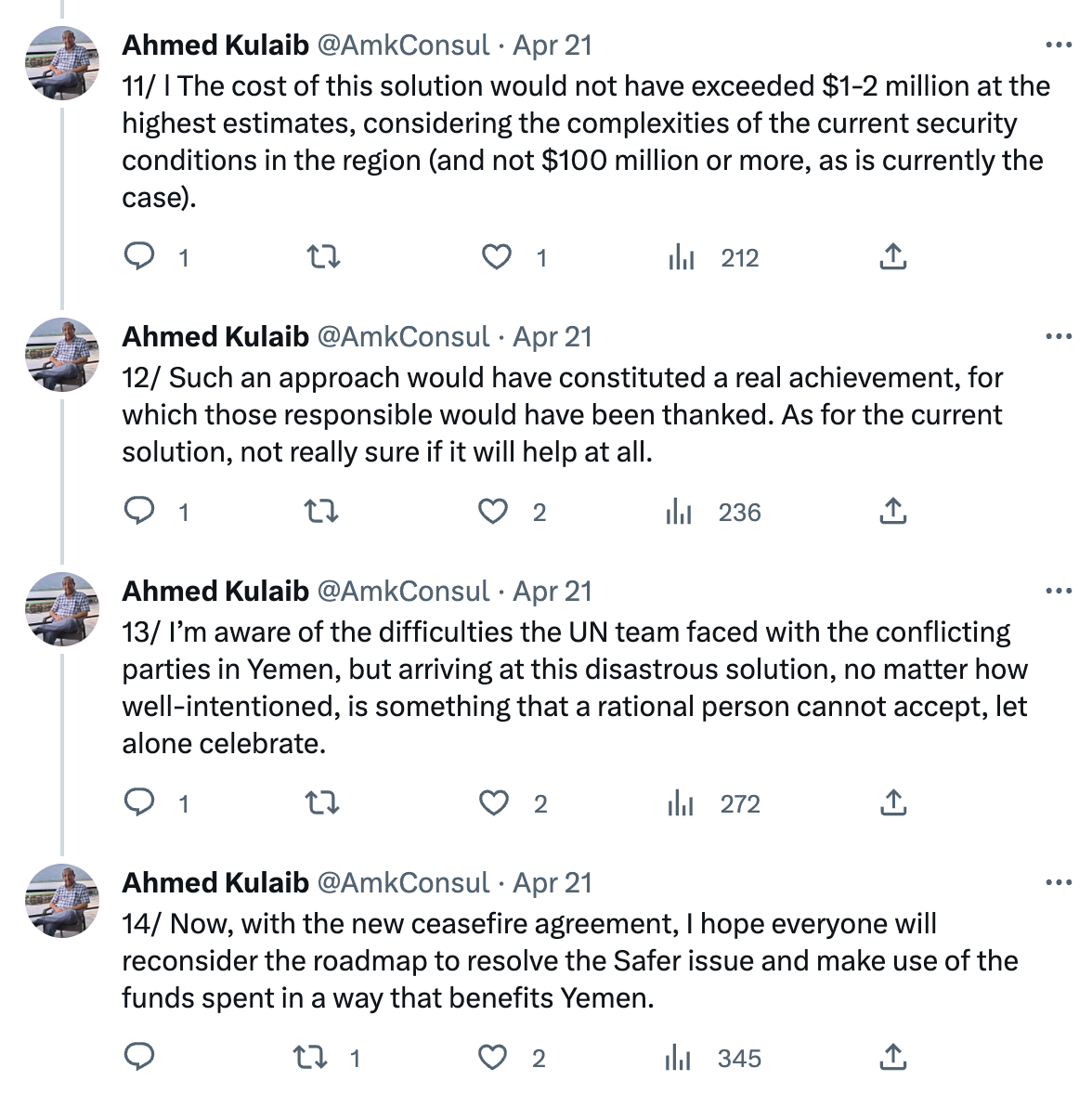

In April, with promising signs around a potential future formal ceasefire, Kulaib laid out what he would like to see occur, reiterating what he saw as the flaws in the UN approach.

Because the UN had gone down the path of securing a replacement vessel, which he says is not really fit for purpose for the offloading of oil, what will remain will be a high cost operational scenario with the potential to become another Safer.

Instead, the priority should have been to sell the oil, most of which belongs to the Yemeni government, and get it away from the area. With his main concern with the Safer being the lack of inert gases on board rather than the thickness of the hull or how the oil had been stored, he wanted to see an inert gas generator installed on board to stabilise the cargo. Other types of inspections could take place to ensure that from a safety perspective the Safer was ready for oil to be sold once agreement had been obtained. The sale could be facilitated through companies in the region, to the wider global market. Once empty of its contents, the danger would then go away.

And just under a week ago, Kulaib reported that the current set of inspections by SMIT Salvage had returned good results on the condition of the Safer for any oil transfer:

The thickness of the steel was within the safety range as he had previously intimated it would be.

The percentage of oxygen in the tanks was only 2% after the injection of inert gas and does not exceed the standard 8%.

He praised the local crew who had maintained with little resources the condition of the Safer.

He has not changed his position on the UN Operational Plan.

There is still a long way to go

Whether it would have been possible to carry out the operation exactly as Ahmed Kulaib wished, with all of the political realities behind getting an agreement in place amongst all parties to the Yemen conflict, is probably now a moot point.

But his criticisms do point to the challenges that the UN operation will face even when they have managed to transfer the oil onto a younger vessel, not a small feat in itself. The oil will still remain in the area until it can be sold, pending agreement between the relevant parties, the latter no small feat either. How the replacement Nautica will handle the Red Sea conditions if the sale drags on remains to be seen. Lasting peace is still not guaranteed either.

Long-time observers and activists following the FSO Safer story are warning that while a lot of hard work has gone into getting to where we are, now is not the time for complacency for the campaign. As long as the oil remains on the water, it is still in danger of spilling into the Red Sea with devastating consequences for the region, environment and indeed the world.